You must not be greatly troubled about many things, but you should care for the main thing—preparing yourself for death. — St. Ambrose of Optina

In our previous post I promised that next time we would look at the care of the body in death and learn about the Orthodox funeral service. But I decided to save that for our fourth and final post in this mini-series.

Because before we get there, to a Christian ending, we need a plan—for ourselves and for our loved ones. In the old days, up to about 150 years ago, nobody needed to make a death plan or worry about end-of-life decisions. People knew what to do when someone died. They knew how to take care of the body of a loved one in the home, they knew the man in town who would be willing to make the coffin, and everyone was buried in the church cemetery or in the family graveyard on the farm.

In the not-very-old days, there was no professional funeral industry. But nowadays, people don’t know how to die, what to do, where to go, what the laws are, who to talk to. This reality is a symptom of our culture’s death denial, as well as a post-Christian society filled with multiple belief symptoms and rituals.

So, if we want to have our bodies cared for in an Orthodox Christian way, it will not happen by accident. We have to make a plan. Rob and I are in the discussion phase of our end-of-life planning, and my goal is to get things in writing and make arrangements within the next year. This will require us to select a funeral home and cemetery, make some payments, and get some legal documents in order.

There are many reasons for doing these things in advance, when we are healthy and mentally and emotionally capable of making wise decisions. But I’ll give you my personal three top reasons for pre-planning, in order of importance.

3 Reasons for Pre-Planning

1. I don’t want my husband and/or children to be forced to make major decisions during a time of mourning.

This is the number-one concern I have. If I die unexpectedly, or after a long illness without making arrangements, the ones I love most will need to take care of everything while grieving and while under a lot of time pressure. It’s important to me that everything is taken care of in advance so that they can mourn without additional burdens.

2. I want an Orthodox Christian death and burial.

An Orthodox death, funeral, and burial are not the norm in the West. And especially for those of us who do not have family members who are practicing Orthodox Christians, our loved ones may choose the easiest, least expensive means of dealing with our corpses: cremation. They might not think of notifying our parish priest. They may plan a celebration of life without any of the rituals of the Church.

3. Pre-planning saves money.

In the United States, the public became aware of predatory practices in the funeral industry in 1963 when author Jessica Mitford published The American Way of Death. And even though there are many good and caring people in the funeral industry—I love the staff members of the funeral home that many of the parishioners at my church use—grieving family members often cannot make wise and rational decisions. They may choose to honor Grandma with the most beautiful, expensive hardwood casket with brass handles and silk lining. They may choose a burial plot in the most scenic part of the cemetery that also happens to be some of the most expensive real estate for the dead in town. They might pay for unwanted embalming services because they think they have to.

But when we plan in advance, we can find inexpensive options. The Orthodox Christian way of interment is now known as “natural” or “green” burial. We’re actually kind of hip, which is weird. I’m pretty sure I want an inexpensive pine coffin, although there are lovely wicker caskets available. My goal is for my body to be put in a simple and biodegradable container. I will know more after Rob and I visit two cemeteries near us that allow natural burial.

In A Christian Ending, Dn. Mark Barna also notes that a funeral home is not legally required, especially if the body is cared for in the home, transported to the church, and on to the cemetery. The funeral industry actually wrote their own government regulations, and funeral homes charge a basic services fee no matter how much or how little they do. For example, in 2015 in Dn. Mark’s area of the country, the basic fee can be $1,500—2,000 just for body transport and the use of a hearse. Ouch.

Some Thoughts about Embalming

Now that I’ve mentioned natural burial, it’s time to talk about another uncomfortable topic: embalming. Embalming is the chemical preservation of a dead body that accomplishes two things: it slows decomposition and also makes the body easier to handle in funeral preparations—such as applying makeup, dressing the body, and any procedures used to make the body more presentable for viewing before burial.

In most parts of the world, embalming is rare or even taboo. But in the US, embalming is quite common among bodies that are not cremated. It is also practiced in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Britain, and Ireland, but not as frequently. And in other European countries, it’s rare.

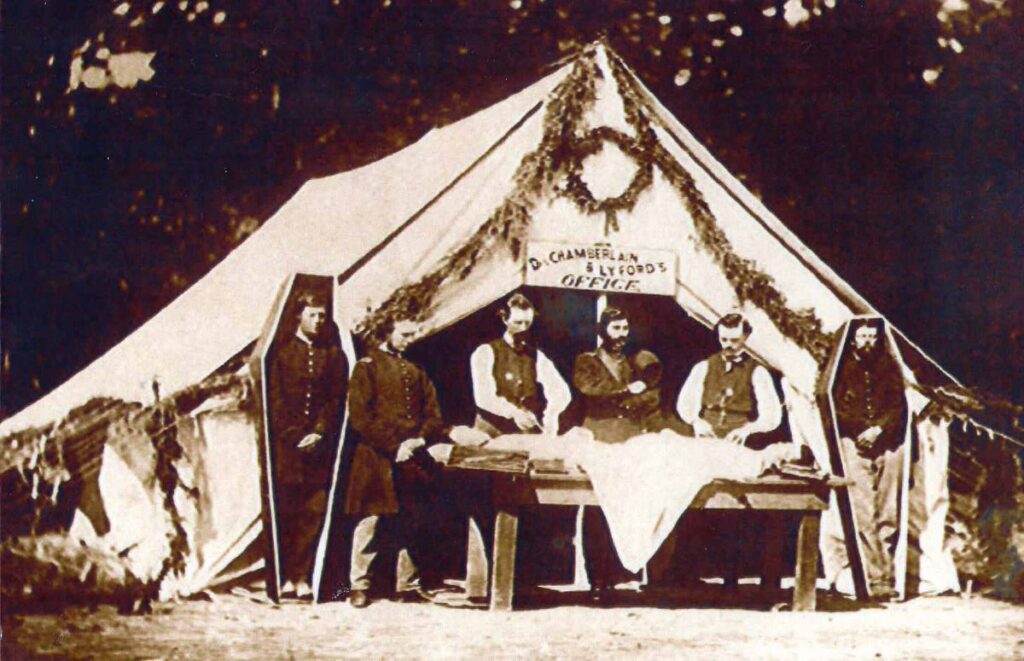

The widespread use of embalming is directly related to its origin and history in the US. Modern embalming began during the Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865. Thousands of young men were dying on the battlefield, many miles from home. Many families had to wait days or even weeks to reclaim the remains of their soldier sons and husbands. In her Ask a Mortician episode, “What Happens to a Body During Embalming?” Caitlin Doughty commented, “It was a good service, giving families a chance to say goodbye.”

Thomas Holmes, known as “the father of modern embalming,” got very rich by offering his services. In this famous photo of him, available on the internet, he and two assistants are standing in front of a tent near a battlefield, working on a soldier laid out on a table. On either side of the tent, two upright coffins each carry a dead soldier, standing and looking lifelike to advertise the quality of his work. Holmes charged $100 per soldier for embalming. For context, in the 1860s land cost $3–$5 per acre, roast beef cost 11 cents per pound, and, depending on the location, rent for four rooms cost $4.45 per month.

Holmes also charged $3 per bottle for his “safe” embalming solution, which used arsenic. In the early 1900s formaldehyde replaced arsenic, and it remains a primary ingredient in embalming fluid today. Although it’s definitely safer than arsenic, formaldehyde is still a known carcinogen; thus embalmers wear personal protective equipment (PPE) when performing the procedure.

Embalming does not disqualify the deceased from an Orthodox funeral, but it is not a preferred treatment for the body. In most Orthodox funerals I have attended, the body has been embalmed. In fact, I’m not quite sure if I’ve attended a funeral where the body had been preserved only with refrigeration and dry ice. For obvious reasons, I’ve never asked the grieving families about preservation choices.

There are times when embalming can be very helpful for families, depending on the circumstances. In one beautiful funeral I attended, the deceased was a beloved priest. Many other clergy attended the funeral, and it took time for them to assemble. Embalming allowed the open-casket funeral to occur many days after his death.

I personally hope to avoid embalming for my own body because of the nature of the process. Chemical preservation and preparation of the body for viewing involves the use of wire, glue, and 2½ – 3 gallons of formaldehyde solution. The solution is injected into the body via a large, hollow needle called a trocar, which is inserted into the stomach repeatedly to allow the highly concentrated solution to fill the body cavity.

And I will stop there. If you are interested in a more detailed, step-by-step explanation, I once again refer you to Ask a Mortician on YouTube. In her episode “Watch Me Get Embalmed (weirdly not clickbait)” Caitlin Doughty and a fellow mortician pantomime the embalming process, explaining the tools and procedures used.

Even with my rather vague explanation of embalming, it’s easy to understand why the Church frowns on the process. As Dn. Mark Barna points out, chemical embalming of the dead is “directly related to our adversarial relationship with matter and nature.” The practice of embalming grew out of warfare and the industrial revolution’s mindset of man versus nature.

So, because one part of my death plan involves avoidance of embalming, what is the alternative? And what if I die in another state, and my corpse needs to be transported? Some funeral homes are experienced in transporting body via air, and a funeral home is needed on the receiving end. Contrary to popular belief, airlines do not require a body to be embalmed, although there are, of course, regulations to be followed.

The website of Southwest Cargo lists detailed rules for transporting human remains. Unembalmed remains must be placed inside two sealed body bags, a sealed casket or metal container, then inside an approved outer container.

A Zeigler case can be purchased for under $500, which is a 20-gauge steel casket with a gasket and lid that is hermetically sealed with screws. Cooling pouches can be placed around the body, and the casket is then placed in a heavy cardboard box and set into a wooden “air tray.” The body is considered cargo, and airlines charge by weight, with a cutoff at 500 pounds. The cost of transport can be thousands of dollars, so this is yet another possibility to think about in death planning.

Putting Paperwork in Place

In his A Christian Ending podcast episode “Initial Preparation of a Body for Burial,” Dn. Mark explains that funeral homes, hospices, and nursing homes are all aware of multiple cultural traditions surrounding death. But they may not be aware that Orthodox Christian practices differ, sometimes radically, from other Western Christian denominations.

Dn. Mark recommends keeping death-care documents on file in the church office and, when possible, at the facility where the death will occur, such as a hospice or assisted living center. When we think of death planning, we naturally think of wills and trusts—the financial part. But there are many other documents to put in place. This can be a bit overwhelming. But the good news is that these forms are available on your state government website. I’ll just give a quick overview here of several documents that can be helpful and can spare our loved ones from a lot of confusion:

1. A healthcare power of attorney

The person who acts in this role will make medical decisions for you if you are incapacitated and unable to make those decisions yourself. The person you appoint does not have to be a family member. It is very important to choose a healthcare decision maker who knows what you want, and that they have the legal authority to make sure your wishes are followed. Alua Arthur, a lawyer, death doula, and founder of the end-of-life planning organization Going with Grace, asks this question of her clients: “Who’s the person you trust to walk into Chipotle and come out with your order correct?” That’s the type of person you need to choose.

2. An Advance Directive

This form describes your wishes regarding resuscitation if your heart stops beating or you stop breathing. It also covers pain management and organ donation. There are actually a lot of what-ifs to consider in situations where injury and disease are involved. The Mayo Clinic offers a helpful online article called “Living wills and advance directives for medical decisions.”

3. Deathcare power of attorney

This belongs to the next of kin under most state laws, but the situation can get complicated, depending on family circumstances and dynamics—such as divorce or relatives who don’t speak to one another. If you are the only Orthodox Christian in your family and your wishes are not placed in writing, your agnostic brother or Baptist sister might make very different choices from what you want.

There are a lot of issues to think about surrounding death and dying. I figure Rob and I will tackle these papers one at a time. A few minutes ago I logged onto www.colorado.gov and found the page “Advance care planning for patients and families.” Your state will offer similar help, although I’m not sure where to direct people outside the US. But a web search is always a good place to start.

Dn. Mark also has a website full of resources, including makers of traditional orthodox burial coffins, at www.achristianending.com.

Making a Death Plan

Once the paperwork is in place, making your wishes known for a variety of scenarios, it’s time to make an actual death plan. There are many ways to approach this, and communication with our family and friends is vital. I like Caitlin Doughty’s recommendations in her video, “Making Your Death Plan.”

1. Communicating your plans

Send an email to your next of kin, a close friend, and the funeral director. The next of kin makes the decisions, and the funeral director finds the paperwork. Make sure that these key people have each other’s cell phone numbers and email addresses so that they can coordinate. Include details such as your choices for pallbearers, the photo you would like to have displayed at the church, details for the mercy meal before the trip to the cemetery, etc.

2. Body stuff

After you die, where and how will your body be laid out for friends and family to visit and say goodbye? A funeral home chapel is common, but it is possible for your body to be prepared in your own home and laid out in the living room for two or three days before the parish funeral, with cold packs and dry ice used for preservation. On Dn. Barna’s website, some Orthodox coffin makers are listed who are able to ship a simple wooden coffin overnight.

This DIY, home-based approach to death can sound unnerving for those of us who are accustomed to the American out-of-sight, out-of-mind approach to death, where the medical and funeral industries take care of everything. But Ms. Doughty, a trained mortician who was a funeral home owner for many years, says in her death-plan video, “I have seen again and again how spending time with the body of a deceased loved one is transformative.”

The more I think about the idea of my body, and the bodies of my loved ones, being displayed in the home, I realize that this is a very human, personal way of dealing with death. It is also the way death has always been dealt with—among family, friends, and community—for thousands of years. We moderns are the ones who are the historical anomaly, and we are emotionally and spiritually poorer for the traditions we have abandoned.

What if I die a terrible death, say, in a car accident, and my body has been mangled? In this situation, embalming might be a good choice. Several formaldehyde-free, biodegradable embalming fluids are available nowadays—usually made from essential oils—that can preserve the body for up to several weeks. I understand that these fluids are also very expensive, but I haven’t been able to find the costs.

One more important body issue: Deal honestly with body size. Are you a very heavy person? Transporting and burying the body of someone who is obese requires more personnel to move the body, a larger casket, and possibly a burial plot that is larger than the standard. More expense is involved here. And families who are too decorous to mention the physical reality of their deceased loved one can, by their reticence, cause problems if funeral home personnel will transport the body. The workers discover that they don’t have the correct-sized gurney or the muscle power needed to lift, and embarrassment and delay are the result.

3. Social media passwords

If you are on social media at all, share your passwords with a trusted friend. He or she can quickly and easily update your social circle with a notice of your death and the funeral info.

4. Natural burial

Cemetery arrangements definitely need to be made in advance. This is something I especially want to take care of for the sake of my children. I don’t want anyone scrambling to find a plot and being forced to make decisions about headstones and all kinds of expensive things.

In Colorado, it is common for caskets and even simple, biodegradable coffins to be placed in a concrete vault under the cemetery lawn, which kind of defeats the purpose of the biodegradable approach. These vaults are mostly for landscaping convenience, protecting the casket from the heavy weight of the earth and the weight of the riding lawn mowers that are used to trim the grass over the graves.

A natural burial, in a grave where the coffin or shrouded body makes contact with the earth, is not available everywhere. Once again, advance planning is important. When you find the cemetery, how do you want your body to be buried? In a shroud or a simple coffin? Do you want a headstone?

5. Contingency plan

As the old saying goes, “Hope for the best; plan for the worst.” What about dying overseas? It does happen, and transporting a body internationally can be a complex process. So, besides praying, “Please, Lord, don’t let me die on a cruise ship,” we do need to think about this. I’m hoping to get information from the staff at the cemetery we choose, because right now I have no clue.

And finally…

6. Comfort & care

What does your ideal death bed look like? For example, if you die after a long illness or a slow decline through age, would you want to die in a hospice, or in your own bed at home? Would you like to be surrounded by your favorite flowers and lit candles, whether wax or electric?

The Orthodox practice of dying includes prayers and the reading of psalms over the body. Would you like to ask some dear friends to take shifts in psalm reading?

Once again, so many things to think about. Planning for our deaths is not only practical and a loving act for our families, it truly is a spiritual practice. It definitely qualifies as “remembrance of death.” So even as we immerse ourselves in paperwork and details, we should be mindful that we are preparing not just for the future of our bodies, but of our souls. Father Evan Armatas, host of the AFR show Orthodoxy Live, once said, “The purpose of the Church is to prepare you for death.” Our bodies will rest in the ground, and they will rise mystically in the general resurrection, and we will stand before God. This is the preparation work of our whole lives.

Prepare your heart for your departure. If you are wise, you will expect it every hour. Each day say to yourself, “See, the messenger who comes to fetch me is already at the door. Why am I sitting idle? I must depart forever. I cannot come back again.” Go to sleep with these thoughts every night and reflect on them throughout the day. And when the time for departure comes, go joyfully to meet it, saying, “Come in peace. I knew you would come, and I have not neglected anything that could help me on the journey.” — St. Isaac the Syrian

***

Next week, in our final blog post about the Orthodox Christian way of death, I want to paint a picture of a beautiful Christian ending filled with family, friends, and faith. We’ll look at the Orthodox prayers at the point of death, the meaning of the Orthodox funeral service, the mercy meal among friends, family, and fellow parishioners, and the burial.

We’ll end this mini-series with a vision for dying and death that brings tremendous peace. The ancient Christian way is deeply human, Christ-centered, honest about the reality of death, and filled with resurrectional hope.

I hope you can join me.