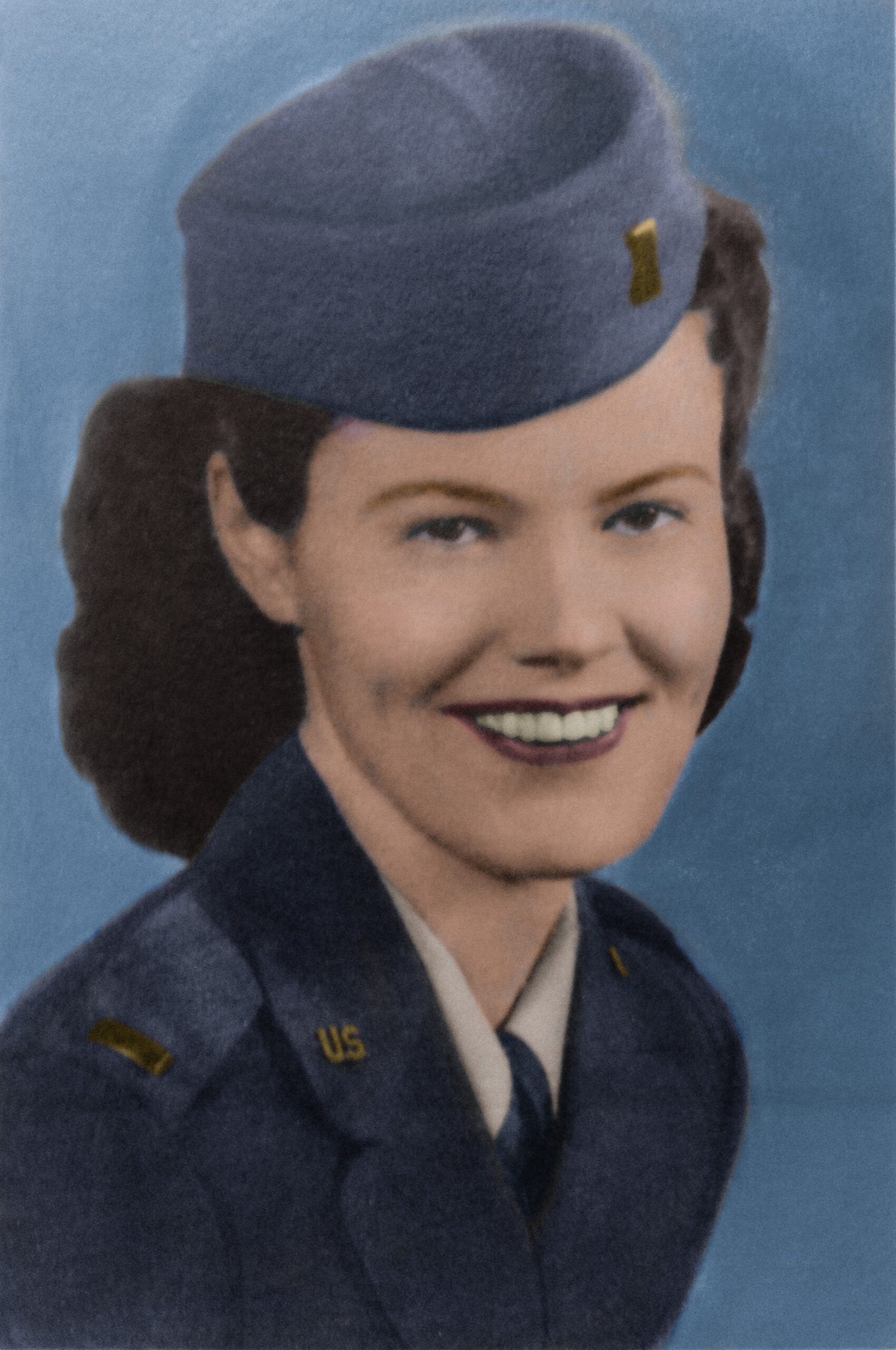

A photo of my late mother holds pride of place in the family room of my childhood home. In the photo, the year is forever 1952, and Second Lieutenant Eleanor Meck, about age 26, smiles at the camera in her Women of the Air Force uniform, a military cap set at a jaunty angle atop her brunette curls.

After Mom died in 2013, my husband Rob, whose photos often grace my blog posts, cleaned up the old black-and-white photo and colorized it, changing the gray wool to navy blue, adding color to her cheeks and lips and brown to her eyes.

She had received her first salute from my dad at Randolph Air Force Base. When Dad unwrapped the framed photo, he sobbed, filled with grief, filled with memories, filled with love.

The photo stayed on a side table in the family room for seven years until my dad’s recent death and remains in the room today. And every morning, until the day he died, my thoroughly Protestant father would gaze at his late wife’s photo and talk to her.

After 60 years of marriage, old habits die hard. Yet his daily conversations with my mother were more than a comforting routine. Dad, who had never once prayed to a saint or venerated an icon, talked to his late wife because he knew, in his bones, that she is alive. This was an unquestioned truth. His behavior was not a theological statement; it was a cry of the human heart and an expression of an inner knowing.

My older brother, raised Methodist and with no theology of saints, occasionally visits our mother’s grave. He tells me that he talks to her about the goings-on in his life and in Dad’s.

You may have done the same, kissing a photo of a loved one who has died, visiting a grave, lovingly caring for a treasured heirloom.

Icons. Relics. Holy places. We all have them, regardless of the theology we profess.

When I told you about my father talking to Mom’s photo, were you suddenly overwhelmed with a desire to barge into that living room, shake your finger in his face, and tell him, “Stop worshiping Eleanor! That’s blasphemy!”? Somehow I doubt it. I think we all understand what he was doing, and why, even if we aren’t able to articulate the emotional logic.

My dad’s and brother’s veneration of a beloved woman named Eleanor is fundamentally no different than the Orthodox Christian veneration of the saints. We talk to the people we love, whether our relatives or our spiritual family, because they are alive. Because we are one in Christ.

For many years I’ve felt that part of our suspicions about praying to saints is a language problem: the phrase “praying to.” But Orthodox Christians don’t pray to saints in the way Protestants use the term. Older uses of the term pray mean “to ask imploringly” or simply to communicate. For example, the seventeenth-century English poet Alexander Pope said, “I am his Highness’ dog at Kew; Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you?”

But this understanding of archaic language is not really helpful nowadays. I have never once said, “Pray tell me, Caitlin, have you cleared the dishwasher yet?” It is more accurate for us to say that we “ask the saints to pray for us,” but we usually shorten the wording to “pray to [fill in saint’s name].”

In their Lord of Spirits podcast, Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick and Fr. Stephen De Young talk about this language issue in the episode, “His Ministers Flaming Fire.” I was so happy to hear a priest, Fr. De Young, admit that the “pray to” language is a problem. Actually, I highly recommend this particular episode of Lord of Spirits for its richly detailed discussion of our connection to the saints.

Still, maybe this practice of talking to dead relatives is just emotional longing. Wishful thinking. Yet this longing is very human and universal. In his book Everywhere Present (Conciliar Press, 2011), Fr. Stephen Freeman writes about an incident when he served as a hospice chaplain:

A young Baptist widow asked of her husband, who had recently died: “Will he be aware of me when he goes to heaven?” To a degree, her question and her anxiety were driven by a two-storey vision of the universe. Her departed husband was going to live “up there.” Would he know what was happening in her life “down here”? (p. 18)

When we long for this connection with those who have passed from this life ahead of us, are we just being sentimental? Where do we find this kind of thing in the Bible?

Jesus Broke the Barrier between Heaven and Earth

In his book Know the Faith (Ancient Faith Publishing, 2016), Fr. Michael Shanbour discusses what he calls the “radical consequences of the Resurrection”: because Jesus conquered death, the separation between heaven and earth has been abolished.

Three of the Gospels record that after Jesus took His last breath, “the veil of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom” (Matt 27:51; also Mark 15:38, Luke 23:45). The veil, or curtain, separated the holy place from the Holy of Holies, and, as Fr. Michael writes, “it symbolizes the barrier between God and man, but also between heaven and earth.” It was torn from top to bottom, meaning that heaven and earth are no longer separated.

A few episodes ago on this podcast we looked at Jesus’ work on Holy Saturday: His descent into hades to free the captives there, after which eyewitnesses in Jerusalem saw the saints walking around in the city. Matthew 27 states, “the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised; and coming out of the graves after His resurrection, they went into the holy city and appeared to many” (vv. 52-53). Jesus united heaven and earth.

In chapter one of his Letter to the Ephesians, St. Paul writes about the many gifts we receive from God through our redemption in Christ, such as forgiveness and grace, as well as God’s purpose “that in the dispensation of the fullness of the times He might gather together in one all things in Christ, both which are in heaven and which are on earth—in Him” (Eph. 1:10).

![]()

Father Shanbour explains,

The natural implication of this unity of heaven and earth in the Church, as attested to by the Scriptures and the saints, is the union and communion shared by those who are “in Christ.” This union transcends death. Death has no more power for those joined to Christ. Because of the Resurrection of Christ, death can no longer separate man from God nor man from his brother in Christ, whether from the living or among the departed. (p. 298)

True, we don’t see people praying to the departed in any explicit way in Scripture. We need to take a step back for a more holistic view. Father Shanbour continues,

The whole context of the Scriptures shows us that through His redemptive work, His Cross and Resurrection, Christ has broken down the barrier between heaven and earth, and therefore between those who are in Christ, whether in heaven or on earth. Most Protestant Christians have not considered deeply these implications of Christ’s Resurrection. (p. 305)

For those of us from a Protestant background, our confessional theology—what we proclaim and say we believe—is that the Church is one, undivided. I was taught this, but it was a theory that didn’t really affect my life or my views of eternity. In the churches I attended over the years, we mostly ignored those who had died in Christ, because in our functional theology—the way we actually lived and thought in real life—we acted as if there were two separate churches, one here and one in eternity.

On an intellectual level, I admired many Christians from the pages of history, but I felt no real connection with them and certainly didn’t think of them in relational terms.

Father Freeman writes,

Those who have died are separated from us in the body—but the Church remains One. There is not one Church on earth and another in heaven. There is one Church, of which all Orthodox believers are members. . . . Such an understanding is only possible where the distance between God and man, between heaven and earth, has been overcome. (p. 16)

The Church is One

We talked a bit about the unity of the Church on earth and in heaven last time in part 1 of “Suspicious of Praying to Saints.” But let me share a story that shows this theory worked out in reality.

Father Freeman recounts his conversation with a monk at Mar Saba, the Monastery of St. Sabbas, located outside Jerusalem:

“We never say that a monk has died,” our guide told us…. He continued, “We always say, in the words of Scripture, that they have ‘fallen asleep.’ But mostly we say this because we see them so often.”

Now I knew I was in a different place.

“You see them?” I asked.

“Sure,” he said. “They appear to the monks all the time. It’s nothing to see St. Saba on the stairs or elsewhere.” The witness of the monk (who happened to be from San Francisco) was not a tale of the unexpected. These were not ghostly visits he was describing, but the living presence of the saints who inhabit the same space as ourselves. It is a one-storey universe…. That which separates the monks of the present from the fathers of the past is very thin indeed. It is not only a one-storey universe, but a fairly crowded universe, at that. (p. 15)

It’s not only monastics who see the saints among us. Everyday believers do too, but Orthodox Christians tend to be a bit shy about sharing their spiritual experiences. They don’t usually draw attention to themselves by proclaiming mystical encounters from the rooftops or embarking on speaking tours. But if you ask around a bit, you will discover that the saints truly are part of this world.

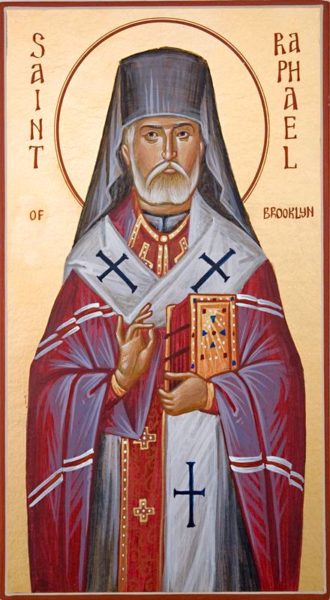

At an Ancient Faith Writing & Podcasting Conference a few years ago in Antiochian Village, Pennsylvania, a group of us visited a small cemetery on the grounds where we could pray at the graves of some heirarchs of the Church, including Metropolitan Phillip and St. Raphael of Brooklyn.

People shared stories, including an incident that had occurred at the camp a few years previously. Some grade-school children had been playing outside, and they ran into the conference center exclaiming that they had seen the bishop.

“No bishop is visiting today,” they were told. But the children insisted that a bishop was walking the campground.

A wise camp worker escorted the children into the conference room, where portraits of past bishops of the Antiochian Archdiocese line the walls. The children looked at the pictures, pointed to the image of St. Raphael, and said, “That’s him! He’s the bishop we saw!”

Saint Raphael fell asleep in the Lord in 1915.

Another American saint, St. John Maximovitch of Shanghai and San Francisco, is known for working so many miracles since his death in 1966 that an entire book is filled with stories of his active involvement in the lives of the faithful. I personally know two people with relatives who experienced miraculous healings through his prayers.

Once again, the saints are active because they are alive. This sounds strange to some of us, but it wasn’t to the early Church.

Saints and Angels in the Early Church

The idea of angels and saints being active and present in the world is not a concept that was introduced in the Middle Ages. The Church’s understanding of heavenly intercession is part of a very early witness, before the division of East from West.

Around AD 253, St. Cyprian, bishop of Carthage, instructed his flock “on both sides” (meaning, on both sides of death) to continue praying for one another from beyond the grave:

Let us on both sides always pray for one another. Let us relieve burdens and afflictions by mutual love, that if one of us, by the swiftness of divine condescension, shall go hence first, our love may continue in the presence of the Lord, and our prayers for our brethren and sisters not cease in the presence of the Father’s mercy. (Letters 56[60]:5)

Clement of Alexandria, whose life spanned the second and third centuries, wrote about angelic intercessions. In his words, the Christian “also prays in the society of angels, as being already of angelic rank, and he is never out of their holy keeping; and though he pray alone, he has the choir of the saints standing with him” (Miscellanies 7:12, ~AD 208).

One of my degrees at Baylor was in religion, and I attended a year of Fuller Seminary before changing direction. I took courses like Patristics and Early Church History, and I read many of the Church Fathers. But I don’t recall reading their words about the intercessions of the saints.

As I’ve looked back on my religious education, I’ve come to realize that just as “the devil is in the details,” it’s often true that the doctrine is in the ellipses—the dots of omission between sentences. In other words, if the theology didn’t fit the institution’s statement of faith, it was either explained away or simply cut out.

This might not be true of all Protestant seminaries, but it fits my experience. For example, Protestants, especially Calvinists, love St. Augustine of Hippo. I remember reading books and articles by the late Chuck Colson, founder of Prison Fellowship, and he wrote often of the tremendous influence of St. Augustine’s City of God on his life and worldview.

But I’ve never seen an Augustine-lover share the following quotes. In The City of God he wrote, “Neither are the souls of the pious dead separated from the Church which even now is the kingdom of Christ. Otherwise there would be no remembrance of them at the altar of God in the communication of the Body of Christ” (20:9:2, AD 419).

Remembrance of the saints at the altar. Does that sound familiar? Last time, we looked at some Scripture verses about the intercession of the saints. Revelation 6 tells of Christ opening the fifth seal, and St. John wrote, “I saw under the altar the souls of those who had been slain for the word of God and for the testimony which they held. And they cried with a loud voice, saying, ‘How long, O Lord, holy and true, until You judge and avenge our blood on those who dwell on the earth?’ (vv. 9-10).

The saints remember us, and we remember them. At least, we have throughout most of history.

The fact that the dead were remembered at the altar during the Divine Liturgy in the fifth century is not something that was mentioned in my Protestant religion classes. Yet St. Augustine affirms that “at the Lord’s table, the clergy ‘commemorate martyrs,’ ‘that they may pray for us that we may follow in their footsteps’” (Homilies on John 84, AD 416).

As Mother Alexandra wrote in The Holy Angels (Ancient Faith Publishing),

The Orthodox Christian, participating at the Liturgy, is not an individual standing alone and solitary. He takes part in the prayers of the Church and the Church prays for him and for the whole world. The Communion of Saints is ever present, for all worship together. There is no division, sinner and saint, beggar and king, layman and priest, the living and the dead and the entire heavenly host—all worship together, side by side in otherworldliness, before the Throne of God. The Christian finds himself in his true native land. (p. 269)

Why Pray to Saints?

Well, it’s one thing to remember the saints and even to acknowledge that they are alive and have some interest in us. It’s a safe, comfortable theory. But why bother to ask for their prayers when we can simply request prayer from the flesh-and-blood people around us?

I can think of three reasons.

1. The saints are influential helpers, not substitutes for God.

In The Orthodox Church: 455 Questions and Answers (Light & Life Publishing, 1988), Fr. Stanley Harakas writes, “Our prayers to saints are as if we were asking an elder brother or sister to speak on our behalf to our parents; or, as if we were asking a fellow employee to intercede on our behalf with our employer. It is not that we can’t speak for ourselves” (p. 187).

![]()

It would be wrong for us to turn to a faith healer and ignore God when we are sick; it is also wrong to turn to the saints and not to God. But every gift, including prayer from our brothers and sisters in Christ, comes from Him. And when we ask for prayer support from those on earth or in heaven, we naturally turn to people with a track record of proven faith. As Abbot Tryphon wrote in his blog post,

When we are in need of prayer we don’t head for the nearest tavern and ask the man slumped over the bar to pray for us (God may not have heard from this fellow for a very long time); rather we ask for prayers of those who are close to God. No one is closer to God than those who’ve lived holy lives, or who have died as martyrs, so we know they are alive in Christ and have His ear. We don’t just ask a friend, we ask a saint to pray for us because Christ is glorified in His saints (2 Thessalonians 1:10). (“The Role of Saints in Our Christian Lives”)

2. The Saints Are in God’s Presence

In verse 12 of St. Paul’s “love chapter,” 1 Corinthians 13, Paul writes, “For now we see in a mirror, dimly, but then face to face. Now I know in part, but then I shall know just as I also am known.”

The saints are “face to face” with God. They are no longer distracted, burdened, and deceived by the needs of family and the temptations of the world. In the midst of our cares, we see truth dimly, in glimpses, and our thoughts are distorted. But, as St. Paul says, the saints know God. Truth is a Person, and they dwell in His presence.

Saint John, the Wonderworker of Kronstadt who died in 1909, wrote,

If we call upon the saints with faith and love, then they will immediately hear us. The faith is the connecting element on our part, and love on theirs, as well as ours; for they are in God, and we are in God, Who is Love. (My Life in Christ, p.345)

As Abbot Tryphon puts it, “Why would we not want to ask for the prayers of those who have already won their place in Paradise, and are already standing before the Throne of God, worshiping the Holy Trinity?”

Our own loved ones are not excluded from this company of heavenly intercessors. Archbishop Kallistos Ware writes, “In private an Orthodox Christian is free to ask for the prayers of any member of the Church, whether canonized or not” (Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church, p. 249), although in public the Church asks prayers only of saints who have been officially recognized. His Eminence gives the example of an orphan who would ask intercessions from the Mother of God and the saints, as well as his parents. My father’s example of talking to my late mother fits here.

3. Saints Are Family and Point Us to God

The saints are not part of some polytheistic belief system, and they don’t exist on their own, apart from God. They are in Christ, alive in His resurrectional power, and they always direct us to the One in whose presence they dwell.

Saint Symeon the New Theologian connects these ideas:

The Holy Trinity, pervading everyone from first to last, from head to foot, binds them all together. . . . The saints in each generation, joined to those who have gone before, and filled like them with light, become a golden chain, in which each saint is a separate link united to the next by faith, works, and love. So in the One God they form a single chain which cannot quickly be broken. (Centuries, 111, 2-4)

I now think of the saints as long-lost relatives whom I discovered late in life. They are part of my spiritual family tree. Even in seasons of loneliness here on earth, we are never alone. Father Alexander Elchaninov of Russia, who entered eternity in 1934, wrote in The Diary of a Russian Priest (SVS Press, 1997):

Man finds his true self in the Church alone; not in the helplessness of spiritual isolation but in the strength of his communion with his brothers—and sisters—and with his Saviour. The Church is a living organism, integrated by the common love, forming an absolute unity of the living and the dead in Christ.

If you haven’t done so already, consider displaying a few icons of beloved saints in your home, in addition to your family photos. In the Horner home, along with Christ, the “sweet kissing” icon of the Virgin Mary tenderly holding Him, and our patron saints, our walls feature icons of St. Ignatius of Antioch, who led me to the Orthodox Church, and St. Irenaeus, a personal hero of mine.

We’ve invited them into our home because they are part of our family. They are part of yours, too.

Beautiful, and so very helpful. Thank you Lynette!

PS – If you ever reply, I was wondering what it was in/about Ignatius of Antioch that led you into Orthodoxy as well as St Irenaeus. 🙂

Thanks Again and Blessings to you and all.

Hi, Pete, I apologize for the late answer! I learned about St. Ignatius and read his letters when I was first looking into Orthodoxy. In his Epistle to the Smyrneans (Ch. 7, Roberts-Donaldson translation), he wrote: “They [the heretics] abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Saviour Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again.” This was in AD 107. I was stunned, especially since I had spent most of my adult life in various forms of the Anabaptist tradition, where communion is just a memorial supper.

I spent three months thinking his words this every day, and because my worldview was a two-storey universe, with St. Ignatius and other believers who had passed on now living in Christ out there–somewhere–it never occurred to me that he might be praying for me and aware that his words had touched my life almost 2,000 years after his martyrdom. Now I believe that not just his writings, but St. Ignatius himself helped lead me to the ancient Church. Of course I can’t prove this, but I feel very close to him. He is definitely on my Black Currant Tea List in heaven. 🙂

And St. Irenaeus (2nd c.) had a brilliant mind and a pastoral heart. Check him out!

Hello Lynnette,

I found your podcasts, or rather I ‘stumbled’ onto them as I was looking for something to listen to on the drive home form NYC to New Hampshire after visiting my son in Queens. Thank you! I came to Orthodoxy 3 years ago after a childhood of Catholicism, being a Protestant (liberal UCC) minister’s wife for 14 years, and 25 years in charismatic Protestant churches. You have broken down so many stumbling blocks for me. Thank you. Your podcasts, and now your blog, is exactly what I have been looking for. No one at church has any idea what I am talking about when I ask about the charismatic elements of praying, speaking in tongues, claiming healing, etc. You have done my homework for me! Thank you. Can you relate if I tell you that I have actually caught myself responding to the Priest with a “Bless you!” after he has blessed me! Oh dear! So much to unlearn.

Yes, I can relate to the fumbles! Do I bow, kiss the hand, hug? And each priest has his own way of doing things. Ack! I thank God that Walking an Ancient Path has been helpful to you.

I think your article is very good. As a cradle orthodox I sometimes think that “those who come to the faith (the Orthodox faith) from another background still have “flaws in their thinking, because it takes a very long time to have an Orthodox mindset.” Your example, that one wouldn’t ask a person who has an alcohol problem is worthy in Christ’s eyes (because of his/her alcoholic problem) isn’t close enough to God to ask for prayers. I understand that you were trying to illustrate the “holiness of those Saints all ready recognized by the Church of Christ.” Whenever my husband and I give a sum of money to a homeless person/ or a beggar on the street corner we always ask the person’s name so that we can pray for him or her, and we also ask that person to pray for us. There are stories from monastics who “were upset with fellow monk who would leave the monastery and get drunk, then return.” The monk who had the alcoholic problem was a man who when he was an infant to keep him quiet, the parents gave “alcohol,” so the baby would sleep and not make noise for the Nazis would hear the crying. Connie

Thank you, Connie. I think it’s beautiful for you and your husband to ask for the prayers of those you encounter on the streets, as well as praying for them. Abbot Tryphon’s point, and mine, is that we seek out people of strong faith when we need intercessions. But I’ll also take all the prayers I can get! 🙂

Just read this incredible post ! Your reflections are greatly appreciated by this reader! May God continue to bless your times of reading, research, and writing!! Most importantly , may He bless your times of prayer!!

Once again, thank you!

With love in Christ ❤️

And thank you again, Andrea, for all your encouragement!

It’s been a joy to join you on this ancient path. I discovered your posts/podcasts midway during lent this year right before we joined the Orthodox Church on Easter Sunday. My husband, two kids, and I started on the path to becoming catechumens in February 2020. I have had a similar path as yours. Raised in the United Methodist Church, graduated from Baylor University, and went to seminary (Duke, 2 of 3 years). My husband got his PhD in Religion (Theology) at Baylor, and after 25 years of marriage, we finally found the church home we have been seeking. I just wanted to say thanks. I’m learning so much from you and eagerly wait for each new post. If you ever want to come visit Yellowstone or Montana, you’re welcome to stay at our house and join us in worship at St Anthony the Great Orthodox Church.

Thank you so much for your kind offer, Molly. I would love to visit Montana, and it would be wonderful to worship with your family! Our paths do sound similar. I was always searching and didn’t know why–I just knew that Jesus wasn’t the problem. And welcome to the Orthodox Church! May you all grow to know God better and more deeply. We have a lifetime journey ahead of us!

Thank you!