Last time I promised an interview with my hubby Rob about our bumpy road to Orthodox Christianity. Well, we recorded the podcast version but had numerous technical problems, including a thunderstorm, a scared doggo whose fast panting in response to thunder showed up on the recording, a recurring buzzing sound, and volume control issues. After numerous delays and attempts to edit and fix the recording, we set both blog post and podcast episode aside. God, in His providence, must have been telling us “no”—or, at least, “not now.” I hope we can make the episode work in the future, but for now I’m making no more promises.

Instead, today I am adding one more episode to my “Stumbling Stones” series, then I will be taking a break for August. In September we will resume with a mini-series on . . . death. Woo-hoo! Mark your calendars for everybody’s favorite topic. We will consider the beauty and resurrectional hope of the Orthodox Christian funeral service and explore what the words in the Divine Liturgy mean when we pray for “a Christian ending.” How does the Orthodox understanding of the human body in life, death, and burial differ from the modern world’s and even from the views of the heterodox Christian world?

Until then, let’s move on to today’s topic.

***

I remember exactly where I was sitting. I was in my first Introduction to Orthodoxy class (I’ve attended several), and I don’t remember what the priest was talking about, but one of the students, an Orthodox convert, said “something something relics.”

I asked, “What are relics?” I knew the word, sometimes applied to an old-fashioned person (“She’s a relic of the past”) or to archaeological finds.

The convert and the priest began talking about the bones of the saints, of miracles wrought through them, and other things that went way over my head.

I was gobsmacked. Bones? Miraculous bones? Bits of human bones in parishes? I’m a relatively educated person, with undergraduate religious and seminary training. But my education was Protestant, and the topic of relics was never discussed, except perhaps in terms of the buying and selling of superstitious items in the Middle Ages.

My head was already spinning, and then the priest’s wife said that the icon of theparish’s patron saint in the narthex was also a reliquary—a container for relics. The icon is surrounded by a riza, which means “cover”—an artistic metal covering that obscures most of the painted surface except for the faces and perhaps hands of the saints depicted there. A sliver of one of the bones of the saint was housed in this silver riza.

I left the room at the end of class, walked down the hallway, and paused at the icon and reliquary with tears in my eyes. I kissed it reverently and walked to my car, filled with wonder. And confusion.

For someone like me, who is from a thoroughly Protestant background and also an American, a geographical reality that only deepens the confusion (we’ll get to that in a moment), the idea that bits of human bone are all over the Orthodox world is bizarre. Maybe even a bit . . . morbid?

And these bones are in every Orthodox parish. Yes, even yours. Relics are ubiquitous.

So let’s start with the obvious question:

What Are Relics?

Relic is the term used for a portion of the earthly remains of Orthodox Christians, usually saints. Relics can also be objects, such as clothing, liturgical vestments, or pieces of the True Cross. The bits of bone from saints are often kept in reliquaries, which are usually ornate golden boxes topped with little glass windows. The windows allow believers to view the small relic and to venerate it by kissing the window. For example, the OCA Chancery on Long Island, New York, features many golden boxes with open lids. Under each lid lies a glass-covered icon of a saint that features a little rectangular window to the left of the image that houses a piece of the saint’s bone underneath.

Sometimes the entire body of a saint is a relic because after death that person has been found to be incorrupt. Incorrupt means that after an Orthodox Christian believer dies, sometimes their bodies do not decay. (Incorruption occurs among Roman Catholic saints as well.) A recent example of this in North America is Bishop John Maximovitch of Shanghai and San Francisco, who was later elevated to sainthood. He died in 1966 and was buried beneath the altar of the Holy Virgin Cathedral. For various reasons, he was not buried for about six days. He was laid out in the center of the nave, and thousands of people came to pay their respects and to ask for his prayers. It was a hot San Francisco summer, and during those six days, his body emitted no odors and gave no other signs of decay. Plenty of photos, security guards, and city officials of the time give witness to this phenomenon.

Compare this to Lazarus in the Gospels, who had been dead for four days before Jesus resurrected Him. When Jesus arrived at Lazarus’s tomb, as recorded in John 11:39, “Jesus said, ‘Take away the stone.’ Martha, the sister of him who was dead, said to Him, ‘Lord, by this time there is a stench, for he has been dead four days.’” Or, as one of my favorite lines in the King James Bible says, “He stinketh.”

But their was no stench around Bishop John. Many people already considered him a saint during his earthly life because of his holiness and asceticism, but this miraculous preservation of his body was an important sign that something special was going on here. (And, to answer the obvious question: No, he had not been embalmed.)

About 25 years later, some damage occurred to Bishop John’s coffin—I can’t quite remember why—and his tomb was opened. Still his body showed no signs of decay, and when clergy lifted him out of the coffin to wash and re-vest his body, his limbs all held together. I have seen photos of his body after decades of burial, and he looks like he is sleeping.

Saint John’s body, a complete, incorrupt relic, now lies in a glass-covered coffin in a beautiful shrine on the right side of the nave at Holy Virgin Cathedral. He is clothed in his bishop’s vestments—clergy are always buried in their vestments for serving the eternal Liturgy in heaven—with a cloth over his face and only his hands showing. His hands look dark and dehydrated, sort of like leather, but they have not decomposed. Since his death, hundreds of miracles have been documented in answer to pilgrims’ prayers.

This example in my own country is one way I learned that miracles are not confined to the Bible, and relics do not belong only to Medieval times. But let’s start with the Scriptures to consider the power of the Holy Spirit in objects and even in dead bones.

Relics in the Scriptures

Saint Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 6:19–20, “Do you not know that your body is the temple of the Holy Spirit who is in you, whom you have from God, and you are not your own? For you were bought at a price; therefore glorify God in your body and in your spirit, which are God’s.”

That was one of the passages I memorized while growing up. A question I never asked myself is, “Is there an expiration date? When do our bodies cease to be temples of the Holy Spirit?” Because of my religious background, I didn’t really think about this. But if I had, I would have assumed that death was the end of this indwelling. I thought that my body, once my spirit leaves it and ascends, is irrelevant. But Holy Scripture and Holy Tradition show us that people and even objects can be filled with the Spirit’s power.

Saint Justin Popovich, archimandrite of the Monastery Ćelije in Serbia, who died in 1979, writes in his article “The Place of Holy Relics in the Orthodox Church,” “Holy Revelation indicates that by God’s immeasurable love for man, the Holy Spirit abides through His grace not only in the bodies of the Saints, but also in their clothing.” We see several examples of this in Scripture.

- 2 Kings 13, verse 8 tells us that the Prophet Elijah “took his mantle, rolled it up, and struck the water” of the Jordan River. The water divided, and he and his disciple Elisha crossed over. Later in verse 14, after Elijah “was taken up into heaven by a whirlwind,” Elisha raised this same mantle, struck the water, and it divided so that he could cross over again (v. 14).

- All four Gospels recount the story of the woman who had suffered from a flow of blood for twelve years. She sought after Jesus, and in the midst of a crowd she “came from behind and touched the hem of His garment. For she said to herself, ‘If only I may touch His garment, I shall be made well. But Jesus turned around, and when He saw her He said, ‘Be of good cheer, daughter; your faith has made you well.’ And the woman was made well from that hour” (Matt. 9:20–22). Three of the Gospels add the detail that Jesus said He had felt power going out from Him (Mark 5:30; Luke 8:45–46; John 8:45–46). Our Lord had not prayed over her, and the woman had not even touched His body. The healing came when she touched His clothing in faith.

- Acts 19:11–12 tells us, “Now God worked unusual miracles by the hands of Paul, so that even handkerchiefs or aprons were brought from his body to the sick, and the diseases left them and the evil spirits went out of them.”

- And in one of the odder stories in the Bible, Acts 5:15 recounts that the people in Jerusalem “brought the sick out into the streets and laid them on beds and couches, that at least the shadow of Peter passing by might fall on some of them.” A shadow isn’t even a tangible thing, yet, as St. Justin explains, “By His inexpressible love for man, the Divine Lord allows the servants of His Divinity to work miracles not only through their bodies and clothing, but even with the shadow of their bodies, which is evident in [this] occurrence with the holy apostle Peter.”

- And regarding the spiritual power of the bones of saints, 2 Kings 13:20–21 tells this unusual story:

Then Elisha died, and they buried him. And the raiding bands from Moab invaded the land in the spring of the year. So it was, as they were burying a man, that suddenly they spied a band of raiders; and they put the man in the tomb of Elisha; and when the man was let down and touched the bones of Elisha, he revived and stood on his feet.

I had read this story about the bones of Elisha many years ago as a Protestant, when I was working my way through the entire Bible. But somehow, because of the filters I carried, I did not stop to think about this. A corpse came back to life when it made contact with Elisha’s bones. I didn’t ask why, probably because I had no coherent theology of the body, and I certainly had no teaching on theosis. I couldn’t conceive of the possibility of someone being so filled with the Holy Spirit that their very bones could be deified.

Weirdly, the idea of an object carrying Holy Spirit power somehow migrated over into the charismatic movement in the US, stripped of its context or any association with the saints. I remember as a child watching a televangelist—I will not mention his name, though I’m tempted—who encouraged listeners to write in and request a piece of cloth. He referred to it not as a relic but as a “point of contact.” People were to take this cloth, which he had prayed over—probably in large piles of squares—and pray with it. Maybe to boost their prayer power or their influence with God? I’m not sure. But I’m pretty sure these cloth squares were offered free of charge, with donations gladly accepted.

These white cloths were a poor substitute for holy relics, yet another interesting example of ancient practices recycled and reinterpreted without any Holy Tradition behind them.

Relics throughout Church History

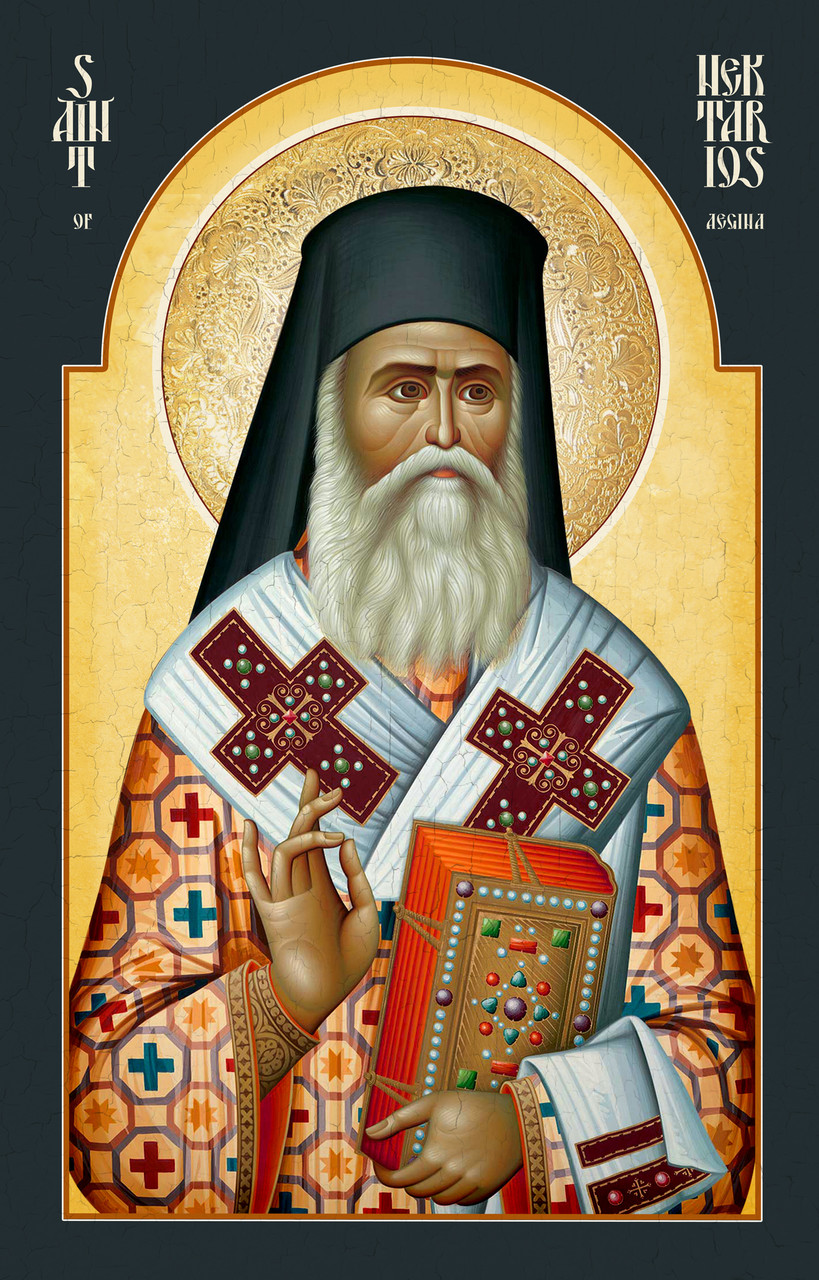

Relics are not new in the life of the Church. The early Christians gathered and treasured the nails used on theCross, Jesus’ burial shroud, and even the Theotokos’s belt. And miracles continue to occur from the bones and clothing of the saints. In one well-known and documented story, St. Nektarios of Aegina, the Metropolitan of Pentapolis, performed his first posthumous miracle immediately after his death at age 74 on November 8, 1920. He had suffered from prostate cancer for two months in a hospital filled with many indigent and incurable patients. In the bed next to him lay a patient who had been paralyzed for years. As soon as the saint died, a nurse and a nun began preparing his body to be transported back to Aegina for burial. While they continued their preparations, they removed the saint’s old sweater and set it on the nearby bed of the paralytic. The man was healed at once and rose from his bed, praising God.

Just as the woman with the flow of blood was healed when she touched the hem of our Lord’s garment, this man was healed by the clothing of St. Nektarios. One of his attending nurses used a bit of cotton to wipe myrrh from the forehead of the saint and anointed her sick husband with it. He was instantly cured and attended St. Nektarios’s funeral. Even the gauzes removed from the saint’s body were fragrant and were buried with him rather than being burned in the furnace with other medical waste.

Relics Are about Life, not Death

The existence of relics, whether incorrupt entire bodies of saints or bits of bone that emit an otherworldly fragrance, reveals to us the power of the Incarnation. In my Protestant past, I knew that Jesus had saved my soul, that by His grace I was spiritually renewed, and that after death I would be resurrected and would receive a new body. But this understanding was incomplete.

The Orthodox Church does not separate the physical and the spiritual. At the Incarnation, Jesus did not redeem just our souls, but matter itself. On the website of the St. Innocent of Alaska Monastery in Redford, Michigan, Sister Ioanna writes the following in her article “Why Relics?”:

Incorruption of relics, like icons, affirm that the physical world indeed does have the potential for being transfigured and resurrected, as it participates in the restoration of humanity to the beauty of the Divine Image and Likeness. The sanctified and transfigured bodies of the saints (whether or not they are incorrupt) are so powerful that numerous miracles occur by means of the saint’s relics, or even by being anointed with oil from the lamps burning by their relics, or from soil from the ground where the saints are or were buried. Of course, most of the saints were also vehicles of miracles while they were yet in their bodies, and this miraculous grace continues to flow from them after their repose.

As podcaster Steve Christoforou says in the episode “Why Relics?” of his Be the Bee podcast, “Relics aren’t about death; they’re about life.” Steve (known to The Lord of Spirits listeners as “the voice of Steve”) noted that early Christians gathered the remains of the martyrs and held liturgies on their graves in places like the catacombs of Rome. These underground liturgies were not just about hiding; these early believers understood that the dead are still a part of the Church. Christians received holy communion over the graves of their brothers and sisters in Christ. Steve explains, “Our Faith ultimately rests on the belief that Christ has defeated death, and that we have no reason to fear death anymore.”

Why Relics Are Difficult to Accept

Even with examples from Scripture and from the life of the Church, it can be difficult to wrap our minds around the idea of relics. I’ve had almost a decade anda half to get used to the idea, so if you’ve never thought about the topic before, it’s okay to struggle with it. You have my permission.

Remember that ignoring or having no understanding of relics is a recent phenomenon, the fruit of a secular worldview and also a Protestant one that minimizes the physical world. In short, only in the last 500 or so years have Christians not venerated the saints and treasured their relics. Not only that, but American society, and perhaps other Western cultures, is big on death avoidance, and the idea of putting pieces of a saint’s bones in a small, fancy coffin is shocking and macabre for many people.

Sister Ioanna writes that there are two major reasons why Orthodox Christians, especially in North America, are indifferent to relics and even ignorant of them. The first reason is a lack of experience and exposure to saints’ relics in America. I haven’t yet been to Greece, but according to friends who have visited, Orthodox shrines and churches are everywhere, and some of these churches feature dozens of reliquaries. Russia and Romania also are blessed with many saints’ relics. So even atheists there must address the existence of relics, if only to dismiss them.

But here in Colorado, not so much. North America is blessed with only three complete relics of saints. The holy relics of St. Herman of Alaska have blessed our continent since 1837, but how many people visit Kodiak Island, Alaska? Saint John Maximovitch is on the West Coast in San Francisco, and the relics of St. Alexis Toth, who died in 1909, now rest on the East Coast at St. Tikhon Monastery in South Canaan, Pennsylvania. North America is a very large continent. If you live in Vancouver, Atlanta, or Denver, you are unlikely to have an opportunity to see a saint’s relics without making a lot of effort.

The second reason for indifference to relics stems from the first: Lack of experience leads to lack of understanding. As Sister Ioanna notes, “It can be difficult to understand something that is outside one’s experience.” Yet relics are not just quaint, ahem, relics of the past. They are integral to the life of the Orthodox Church. Even in Canada. Even in the US.

Relics Are Vital to Orthodox Christianity

The saints are alive in the presence of God, and they have no need for our attention at all. But the Church glorifies saints for our benefit. Relics bear witness to the truth of Orthodox theological and spiritual principles, especially of theosis. Saint Justin Popovich writes that the saints’ holiness, of both soul and body, comes from their grace-filled lives of virtue in the Church, the Body of Christ:

In this sense, holiness completely envelopes the human person—the entire soul and body and all that enters into the mystical composition of the human body. The holiness of the Saints does not hold forth only in their souls, but it necessarily extends to their bodies; so it is that both the body and the soul of a saint are sanctified.

Historically, churches have been built above the graves and relics of the saints. This has been the norm of Christian faith and practice, despite the last 500 years of Protestant rejection, and the tradition of venerating the saints’ relics is a part of every Orthodox parish, including yours and mine. Sister Ioanna notes, “Since we cannot usually go to the martyred saints’ graves, one might say that the Church brings the martyrs’ relics to us.”

The altar of every consecrated Orthodox church includes relics, and on that altar lies an antimension, which in Greek means “instead of the table.” The antimension is a cloth rectangle of linen or silk that is covered with representations of Christ’s entombment; the four Evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; and scriptural passages related to the Eucharist. Usually lay parishioners see the antimension up close only on Holy Friday, after the service of taking down Jesus from the Cross, when we venerate it on the wooden bier that represents Christ’s Tomb.

A small relic of a martyr is sewn into each of these cloths. My parish is blessed with bits of bone from the early fourth-century martyr St. Boniface of Tarsus and from St. Kyriacos, a boy of about three who in the late third century was martyred along with his mother, St. Julitta. I can’t remember if their relics are in the altar or the antimension or both.

With the placement of relics in every parish, to this day every Divine Liturgy is grounded on the truth of the resurrection and sanctification of all believers. Not even death can change the reality that the saints’ bodies are living temples of the Holy Spirit. In answer to my question, there is no expiration date for the presence of God in His people.

The Church Provides Proof of the Holiness of Relics

From apostolic times forward, believers have treasured the relics of St. John the Baptist and the apostles, preserving them with reverence. During times of persecution Christians were careful to collect the remains of the bodies of the martyrs for reverent burial and sometimes for hiding them in their homes.

Saint Justin gives examples of Fathers of the Church from the fourth century who have affirmed the holiness of relics:

- Saint John Chrysostom preached a eulogy for St. Ignatius of Antioch, describing how the people rejoiced when his remains were brought through their cities on the way back to his home of Antioch:

For how do you think that they behaved when they saw his remains being brought back? What pleasure was produced! How they rejoiced! With what laudations on all sides did they beset the crowned one! For as with a noble athlete, who has wrestled down all his antagonists, and who comes forth with radiant glory from the arena, the spectators receive him, and do not suffer him to tread the earth, bringing him home on their shoulders and according him countless praises.

- Saint Ephraim the Syrian wrote of the departed saints: “Even after death they act as if alive, healing the sick, expelling demons, and by the power of the Lord rejecting every evil influence of the demons. This is because the miraculous grace of the Holy Spirit is always present in the holy relics.”

- Saint Ambrose, on the finding of the relics of Ss. Gervasius and Protasius, wrote:

You know—indeed, you have yourselves seen—that many are cleansed from evil spirits, that very many also, having touched with their hands the robe of the Saints, are freed from those ailments which oppressed them. You see that the miracles of old times are renewed, when through the coming of the Lord Jesus grace was more abundantly shed forth upon the earth, and that many bodies are healed as it were by the shadow of the holy bodies. How many napkins are passed about! How many garments, laid upon the holy relics and endowed with the power of healing, are claimed! All are glad to touch even the outside thread, and whosoever touches it will be made whole.

- Saint Augustine, who is quite beloved among Calvinists, wrote something about miracle-working relics that they probably do not quote:

To what do these miracles witness, but to this faith which preaches Christ risen in the flesh and ascended with the same flesh into heaven? . . . For if the resurrection of the flesh to eternal life had not taken place in Christ, and were not to be accomplished in His people, as predicted by Christ . . . , why do the martyrs who were slain for this faith which proclaims the resurrection possess such power? . . . These miracles attest this faith which preaches the resurrection of the flesh unto eternal life.

- Finally, the Orthodox Christian Church is known as the Church of the Seven Councils. In 787 AD, AD, the Fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council made the following declaration:

[Icon of the Seventh Ecumenical Council available from Uncut Mountain Supply]

Our Lord Jesus Christ granted to us the relics of Saints as a salvation-bearing source which pours forth varied benefits on the infirm. Consequently, those who presume to abandon the relics of the Martyrs: if they be hierarchs, let them be deposed; if however monastics or laymen, let them merely be excommunicated.

Ouch. There can be no doubt that relics have always played an important part in Christian worship, until very recently.

A Foretaste of Heaven

When we venerate relics that have been brought to our parish during a service, or when we make a pilgrimage to venerate relics, we find that they bolster our faith and encourage us to press forward in Christ, knowing that death is not the end, but a glorious beginning. We see these pieces of bone that should have disintegrated long ago, and we are reminded of the power of God. And if a relic exudes an indescribable fragrance—a common phenomenon that is physically impossible—we are reminded that our understanding is limited, and that God and His works among His saints are mysteries.

Sometimes the reality of the relics themselves defies explanation. Steve Christoforou tells of his own experiences on pilgrimage: In Thessaloniki he venerated the relics of St. Demetrios, who is the patron of that city. The saint’s relics streamed fragrant myrrh. On Mount Athos he venerated the hand of St. Mary Magdalene, which has remained incorrupt for 2,000 years and is warm, like a living hand.

Closer to home, a small relic of St. Ignatius of Antioch is kept in the chapel of Antiochian Village in Bolivar, Pennsylvania. Sometimes it exudes a beautiful fragrance. I listened to a monk from St. Tikhon’s Monastery in Waymart, Pennsylvania, describe a room where some relics are kept as smelling like the Garden of Eden.

I have personally experienced this mystery only once so far in my life. A few months ago Bishop Constantine of the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Denver came to a Vespers service at my parish and brought along with him a piece of the True Cross that had been given to him by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. It was housed in a square, golden reliquary, and we were given an opportunity to venerate it after the service.

I had no expectations as I walked up to the reliquary to kiss the glass over the piece of the Cross. This is important—there was no placebo effect going on. I was curious to see it and wanted to venerate it properly and with reverence. But as I leaned over that tiny piece of the Cross, I inhaled a beautiful fragrance. I would describe it as floral, but it was purer and more potent than any perfume.

After the service I asked Rob if he had detected this scent, but he hadn’t inhaled when he venerated. He thought maybe some incense lingered on the box, but I know the fragrance of incense, and this smelled nothing like it. Also, metal doesn’t hold odors. I asked Bishop Constantine about it, and he confirmed that the relic is indeed fragrant.

Once again, this type of thing is physically impossible apart from the power of Christ. We think of these mystical things—incorrupt relics, otherworldly scents, healings through the prayers of long-dead saints, and icons that stream myrrh—as supernatural because we live in a world tainted by sin and death.

But in the Incarnation, Christ came to save not only our souls, but our whole selves. Saint Justin writes,

The Lord Christ has come to deify, to make Christ-like, the entire man, that is, the soul and body, and this by the resurrection, insuring thereby victory over death and eternal life. No one ever elevated the human body as did the Lord Christ by His bodily resurrection, the ascension of His body into heaven, and its eternal session at the right hand of God the Father. In this way, the Resurrected Christ extended the promise of resurrection to the nature of the human body—“having made for all flesh a path to eternal life.”

As Steve notes, miraculous relics “are all perfectly natural if we remember that death has been defeated, that Christ is risen.” Relics, he says, are “a beautiful way to receive God’s grace and a living reminder that nothing is powerful enough to overcome God’s love. Not even death.”

***

As I noted at the beginning of this post, I will be taking a break during the month of August to prepare some episodes on the Orthodox approach to death, the care of the human body, and the meaning of “a Christian ending.” Until then, have a wonderful month. I hope you can join me.

***

[If you prefer listening instead of reading, Walking an Ancient Path is available in podcast format on the Ancient Faith app, Apple podcasts, Spotify, and a variety of other places.]