I recently read that “Lord, have mercy” is sung over 60 times in the average Orthodox Sunday service. I did a quick search in the text of a recent Divine Liturgy and counted 44. Regardless of the exact number, we sing these words, in English and in other languages, a lot.

Some of our services require “Lord, have mercy” to be said 40 times in a row. This practice earned a joke on a Pinterest board called “Eastern Orthodox Ryan Gosling.” I get a kick out of this one—it features various photos of the actor with captions that begin with “Hey, girl,” and end with very in-jokey Orthodox lines, like, “Hey, girl, I’d totally switch calendars for you.” One of them refers to all the repetition in these services with “Hey, girl, can I just say I love you . . . 40x.”

“Lord, have mercy” is a good prayer. A nice prayer. Short and memorable. But, as I’ve mentioned before, I sometimes have difficulty turning off my inner editor. I’m always looking for ways to trim excess verbiage and unnecessary repetition. I mean, we get it. Why can’t we just pray for mercy once or twice—maybe three times for Trinitarian emphasis—and move on? Isn’t 60 Lord-have-mercies—or even 44—a bit excessive and, well, unnecessary?

Mercy in the Gospels

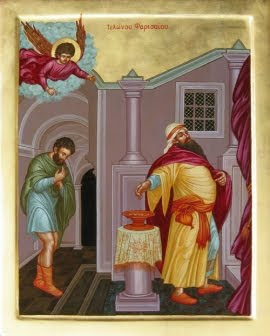

Leaving the repetition aside for now, one of the many wonderful things about this simple prayer is that it is clearly a biblical prayer, most familiar in Jesus’ Parable of the Publican and the Pharisee, which we celebrated Sunday. The Pharisee, convinced of his righteousness, stands before God in the temple and proudly recounts his ascetic feats, but the publican, or tax collector, can muster only a few words with downcast eyes: “God, be merciful to me, a sinner.”

He is not the only one to pray this prayer. In the Gospel of Matthew, several people cry to the Lord for mercy:

- The Canaanite woman whose daughter was “severely demon-possessed” persisted in her plea of “Have mercy on me, O Lord, Son of David!” (Matt. 15)

- The father whose epileptic son was thrown into fire and water by a demon pleaded with the Lord, “Have mercy on my son.” (Matt. 17)

- Two blind men followed Jesus, crying out to Him, “Son of David, have mercy on us!” (Matt. 9)

- Two other blind men sitting by the road to Jericho, surrounded by a crowd who tried to shush them, determinedly called out over and over, “Have mercy on us, O Lord, Son of David!” (Matt. 17)

All these people received the healing that they asked of Jesus.

This prayer of the repentant publican is the basis for one of the most precious prayers of the Orthodox Church, the Jesus Prayer, which is a vital part of Orthopraxy, the everyday life of faith. This prayer asks for nothing but God’s mercy: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner,” or the even shorter version of “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.” (The Jesus Prayer is a topic that is worthy of its own future episode.)

In his article “Kyrie Eleison, Lord Have Mercy,” Father Anthony Coniaris noted, “Without this prayer Christianity would be a philosophy, a history, a code but not a religion that saves.” It is our recognition of our own fallenness, of repeatedly missing the mark, that keeps us asking for mercy and forgiveness rather than simply practicing a code of ethics.

Mercy in the Services of the Church

During the Triodion period—the three weeks of preparation before Great Lent begins—something quite deliberate happens at each Matins service. After the Gospel reading, we pray along with Psalm 51 (numbered 50 in the Septuagint). It is one of the most-used Psalms in Orthodox services and begins with “Have mercy on me, O God, according to Your great mercy; and according to the abundance of Your compassion, blot out my transgression.” A moving hymn of repentance follows this psalm of repentance:

Open to me the gates of repentance, O Giver of Life, for early in the morning my spirit hastens to Your holy temple, bringing the temple of my body all defiled. But as one compassionate, cleanse me, I pray, by Your loving-kindness and mercy.

And another hymn after that says:

When I ponder in my wretchedness on the many terrible things that I have done, I tremble for that fearful day, the Day of Judgment. But trusting in the mercy of Your compassion, like David I cry to You, “Have mercy on me, O God, according to Your great mercy.”

It seems that everywhere we look in Orthodoxy, we find a cry for mercy. So it’s important to step back and take a look at what this word actually means, because often familiarity and repetition, and especially incomplete and erroneous theology, cloud our minds. In the Christian West, mercy carries strong juridical connotations. We think of a judge showing mercy, meaning that he gives a lighter sentence than expected for a crime. In this interpretation, mercy is basically a withholding of punishment for sin.

Especially for people from a Reformed Christian background, these judicial undertones in the English word mercy run deep. John Calvin studied law, and his law-and-punishment background comes through in his theology.

The visual illustration of mercy that often trickles down to the Protestant laity—and believe me, I speak from personal experience—is of God as a stern, bearded judge—think Michelangelo’s work on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel—who also is very magnanimous if we beg for mercy before he pronounces His sentence. In His mercy He refrains from punishing us as we deserve, and we breathe a sigh of relief. (I’m not talking about the Last Judgment here, but of our everyday life of sin and repentance.)

Catholics experience a similar struggle; sin is viewed in terms of crime and punishment, and mercy is an escape from at least some of that punishment.

Now, I admit that my understanding of mercy may have been a reflection of the muddle in my own mind as I grew up, but those juridical metaphors were present in a lot of the teaching I received over the years.

I’m not alone in this. About a decade ago a young friend of mine was inquiring into the Orthodox Faith, and she really struggled with the frequent repetition of “Lord, have mercy.” She didn’t have words to explain why, but I think an unhealthy dose of Calvinism in her grab-bag theological background, in addition to a chaotic and judgmental home life, created a negative image in her mind and heart. Begging God for mercy during Liturgy made her feel that God was always angry at her.

Author Frederica Mathewes-Green admits that, like my young friend, she found the prayer of “Lord, have mercy” annoying at first. In her series of short, informative videos on YouTube called Welcome to the Orthodox Church, which I highly recommend, she addresses the question, “Why Do Orthodox Christians Repeat ‘Lord Have Mercy’?”. She recalls, “It sounded like groveling. It sounds like we’re so afraid that God isn’t going to forgive us that we have to keep begging for mercy.”

So, what exactly is mercy? And why does the Orthodox Church keep begging God for it?I like the explanation from the book Orthodox Worship by Benjamin D. Williams and Harold B. Anstall, available from Ancient Faith Publishing, which I have quoted in the past. It’s worth repeating:

The word mercy in English is the translation of the Greek word eleos, and it has the same ultimate root as the old Greek word for oil, or more precisely, olive oil, a substance which was used extensively as a soothing agent for bruises and minor wounds. The oil was poured onto the wound and gently massaged in, thus soothing, comforting, and making whole the injured part. . . .

The Hebrew word that is translated as eleos (mercy) is hesed, which means “steadfast love.” The Greek words for “Lord, have mercy,” are Kyrie, eleison—that is to say, “Lord, soothe me, comfort me, take away my pain, show me Your steadfast love and Your compassion.”

Thus, the word mercy does not refer so much to justice or acquittal—a very Western interpretation—but to the infinite loving-kindness of God and His compassion for His suffering children. It is in this sense that we pray “Lord, have mercy” with great frequency throughout the Divine Liturgy. (pp. 123-124)

This is a radically different understanding of mercy than that of a defendant standing before a judge, hoping for a favorable ruling. The picture of mercy rooted in eleos, healing oil as a balm for the wounded, brings to mind the well-loved verse from Psalm 23:

You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies;

You anoint my head with oil;

my cup runs over.

Surely goodness and mercy shall follow me

All the days of my life;

And I will dwell in the house of the Lord

forever. (vv. 5-6)

Williams and Anstall continue,

God is love: God is all-compassionate, all-knowing, and all-understanding. The pleas for mercy, therefore are asking God merely to be Himself to us and to lift us up—who are fashioned in His image—that we may come to know Him and to do His will. (p. 135)

When we grasp the proper understanding of mercy as God’s healing, kindness, and compassion, we realize that mercy is exactly what we need from Him. Again and again. Khouria Frederica notes that Eastern Christianity takes sin seriously: “Sin damages us. Sin is sickness. I like to say sin is infection, not infraction. It’s not breaking a rule. It’s participating in this fog of debilitating evil that surrounds the world and affects all of us.”

The Church Fathers write often of the nous, which is our receptive, perceptive mind that has been damaged by the Fall and also by our own sin. Khouria Frederica says that when we pray “Lord, have mercy”:

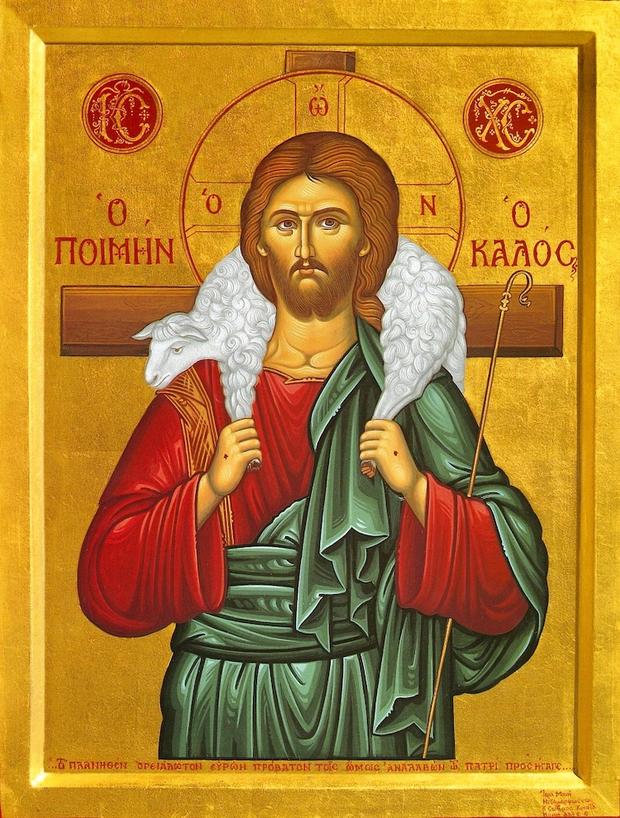

We’re asking for our minds to be enlightened. For us to be able to see reality more clearly, to see where God is at work, and to respond to His calling. That’s why we ask for mercy. Because we take sin seriously—not as a bad deed that God’s going to punish, but as a kind of disease that infects us. We want to be freed from our illness, like so many people who spoke to Jesus as he passed by and cried out, “Lord, have mercy.” That’s why we ask for mercy as well.

The Eastern Church’s understanding of God’s mercy is so tender, abundant, and life-giving. In comparison, the common Western idea of mercy feels thin, withered, and miserly—like crumbs from the Master’s table.

When we pray together for mercy after each petition in the litanies, we are not asking God for a reduced sentence when he punishes us for our sins, and we are certainly not asking for justice. Father Coniaris notes,

We dare not stand before the throne of God and ask that we be given what we deserve. Our only cry is, “Lord, be merciful.” And the miracle is that there is mercy. At the very heart of the universe beats the heart of God’s love. “I tell you,” said Jesus about the publican, “this man went down to his house justified rather than the other.”

With each “Lord, have mercy,” we are asking God to anoint us with the oil of His compassion and healing. St. Isaac the Syrian once said:

Never say that God is just. If he were just you would be in hell. Rely only on His injustice which is mercy, love and forgiveness. “Have mercy upon me, O God … according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions.”

When I pray for myself and for others, I can lapse into the habit of telling God about the details of various difficult situations, as if He doesn’t know already, and then waste a lot of time and energy stewing over the problem rather than actually praying. But when I simply pray with intention and love, “Lord, have mercy on me, and on this person and on that person…,” I am really asking the Lord, in the words of Williams and Anstall, to soothe, comfort, take away pain, and show His steadfast love and compassion in each circumstance.

St. John Chrysostom writes,

Remain in our Lord God until He shows compassion on us. Ask for nothing else other than mercy from the Lord of Glory. When you seek mercy, do so with a humble and contrite heart, and cry out from morning until evening, and if possible all night long.

The prayer of “Lord, have mercy” is indeed a good prayer. A nice prayer. Short and memorable. And given the riches that it contains, what more needs to be said? This simple, short prayer encompasses our personal needs and the needs of the world.

Our job, during the Liturgy, is to bring our attention back and back again to Christ, as the priest’s words remind us: “Let us attend,” or “Let us be attentive. Then, together, “Again and again, in peace, let us pray to the Lord.”

How much mercy does one person really need? A lifetime supply—every hour, every minute of the day. In faith, may we all ask for and gratefully receive the abundant mercy that God, in His infinite grace and compassion, will give to us.

***

I don’t yet have a title for our next episode—I’m deciding between two topics—but I’m busy working on it. I hope you can join me.

As an adult convert, I too had a little difficulty with this prayer. Here’s how I settled it. ‘God, please take over. You’re a lot more loving and kinder than I am.’.

As an alcoholic I use to beat myself up mercilessly all the time. Learning not to do so was very difficult. Orthodoxy and this prayer for mercy helped me immensely.

STEP 3 ~ Made a decision to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God as we understood Him.

You have Saved Me, Changed Me and Taken Care of Me. Please continue to love me more than I can love myself.

Crude and simple I know. But, it works for me.

Not crude at all! And simple is good. 🙂

Thank you for this beautiful explanation of mercy. I had wondered about the repetition of “Lord have mercy”, although I’m beginning to realise that everything in Orthodox practice has a purpose/ history.

I’m enquiring re Orthodoxy. My background is AOG, so a stern, judgemental “god” who chooses some for damnation wasn’t taught to me. Nevertheless, the only definition of “mercy” and “salvation” was based on the legal metaphor.

I had never heard of that explanation of mercy before. It is wonderful and astonishing to discover this way of viewing what Christ did on the Cross and does for us today.

May God bless you in your journey with Him, Anthea!

Cradle Orthodox don’t necessarily get this right either. It’s good to read this post! And now Ryan’s meme make more sense 🙂

True. I think we’re surrounded by a lot of legal—and legalistic—views in our culture. It tends to seep in everywhere. 🙂

Once again, you open our eyes by slowly peeling back those onion layers with tenderness and much care. In doing so, you bring to light so much wisdom with love and prayer while being mindful of extending God’s mercies to your readers. Neither my converted husband (constantly reading about our faith) or this cradle O had ever read this before!! Thank you for sharing Our Faith by your reading, studying, and writing! May God continue to bless and keep you always in His Care and Mercies 🙏. With much love in Christ and Greek hugs, AT

The world needs more Greek hugs! 🙂 Thank you, Andrea.

Thank for such a wonderful and enlightening article.

You’re welcome! Thanks for commenting.

Very very new Catechumen here. Can I say how grateful I am to you for these articles (I’ve been bingeing)? This one in particular made me cry in joy and relief. I grew up gaining quite a bit of salvation insecurity hearing about an angry (and narcissistic) God, so your words are encouraging to me. I have so many reasons to be on this path to Orthodoxy, but perhaps the truest (certainly the least egocentric) has nothing to do with my multiple griefs with Protestantism; it is this prayer. The spirit of it is of a person who understands he is sick and in need of healing; blind in need of sight. Years ago I used this prayer in a piece I composed in a college project. And it stuck in my heart since then. I daresay the Lord used it to lead me to where I am now. Thanks be to God!

Yes, thanks be to God! Thank you for sharing your beautiful story. Truly we need God’s mercy every moment of our lives.