As we’ve been going through the nine parts of the Divine Liturgy, I’ve been using the metaphor of hiking a trail because the Liturgy truly is a mini spiritual journey within our larger spiritual journey of life. And of course, because of where I live, I keep referring to hiking in the Rocky Mountains rather than, say, the Appalachians or the Northern California coast.

In the Rockies of Colorado there is one famous trail that takes most of the day to hike. I think it well reflects our Orthodox liturgical journey: the trek up Grays and Torreys Peaks. Hikers in the Rockies who hope to scale all of its “fourteeners” (mountains that are at least 14,000 feet above sea level) often begin here, because these two peaks are connected by a saddle of land. For those who aren’t too tuckered out after making their way up the first mountain, they can cross over and conquer two mountains in one day. Torreys Peak is one of the goals of this particular hike, but it is not the highest point. Grays is the true summit.

Just as Torreys is not the high point of this hike, the Bible—its reading and proclamation in the sermon—is not the high point of the Divine Liturgy in the same way as it is in Protestant traditions. The Bible is very important, of course: in every Liturgy we prepare ourselves for the reading of the Scriptures and are instructed to attend carefully to the words, especially the Gospel reading.

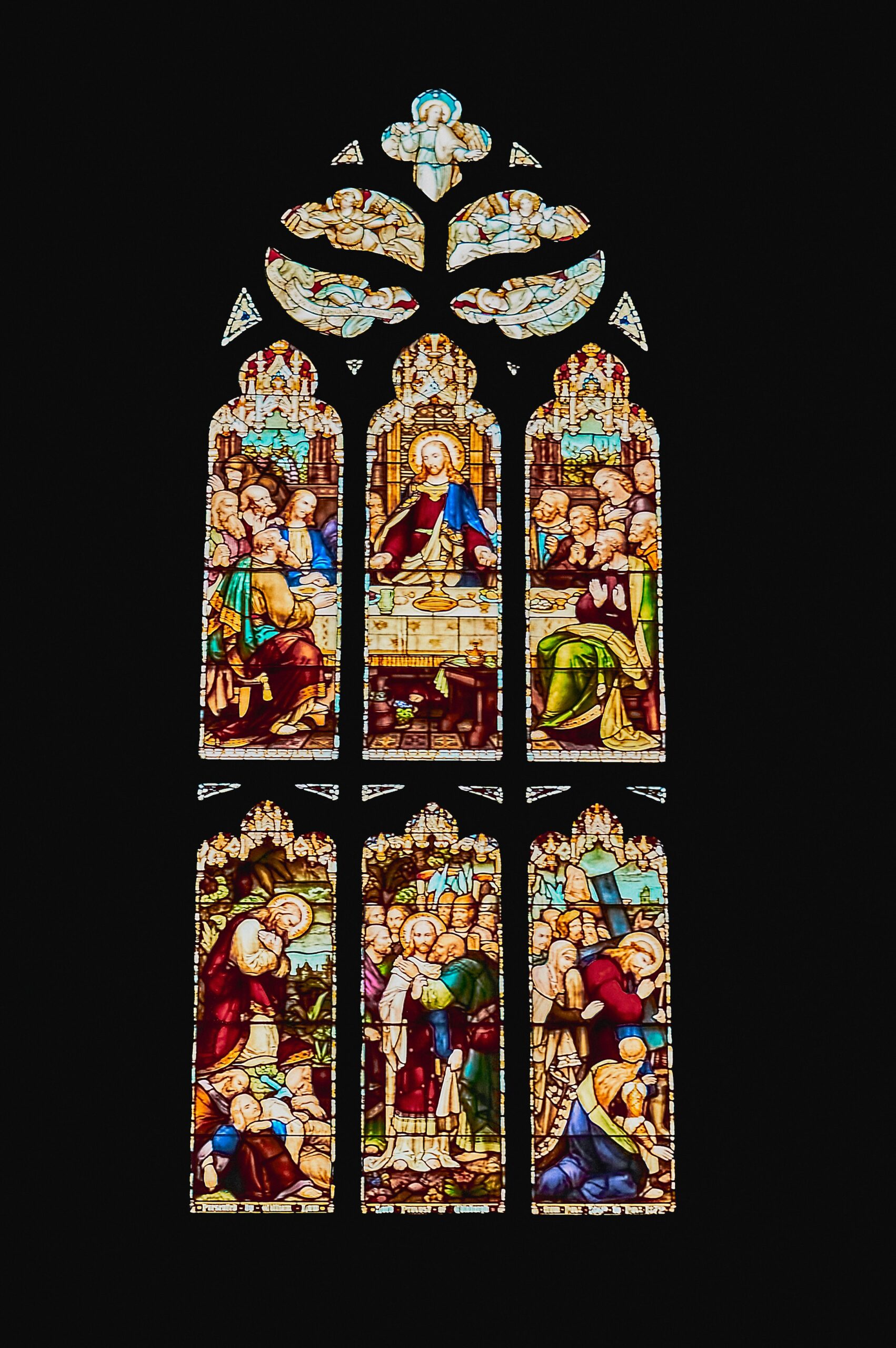

But the Scriptures have an additional purpose beyond their teaching function: to prepare us for the second leg of our liturgical journey, the Liturgy of the Faithful, and its summit, the Eucharist—receiving Christ’s Body and Blood in the consecrated bread and wine. The written Word of God is a vital part of this ascent, but the presence of the Living Word of God, Christ Himself, is, like Grays Peak, the summit. In worship, it is the destination of our corporate journey.

The importance of the Eucharist, which is served at every Divine Liturgy (celebrated on Sundays and often on weekdays and Saturdays), cannot be missed. Its centrality—its inescapability—can be jarring for those of us from heterodox backgrounds who communed infrequently and even casually in the past.

In every Divine Liturgy we proclaim together that the King of kings and the Lord of lords is among us, and by His grace we mystically partake of His Body and Blood. As we considered in the earlier post “Traveling Companions on the Journey,” He is escorted by angelic hosts, and as His people, we set aside all of our earthly concerns and worries, making serious preparations in order to receive Him.

Body and Blood or Memorial Supper?

In the anaphora (literally, “offering”), the priest asks for God’s power to transform our offering of bread and wine into the Body and Blood of Christ, reciting Jesus’ “words of institution”: “Take! Eat! This is My Body. . . . Drink of it, all of you! This is My Blood. . . .”

The priest is not chanting some sort of formula, like a bit of magic that effects physical change. He offers the words as a powerful reminder that Jesus Himself authorized these gifts. In obedience we offer the bread and wine as a memorial—a calling to mind, or anamnesis—to Him.

The majority of Evangelical churches I have attended taught that Communion is merely a memorial supper, but this very literal approach to the word anamnesis and to the sacrament itself is too small, too narrow an understanding of the Mystery. In fact, there is no mystery to this view at all. Communion becomes an intellectual exercise, even if a prayerful one; it is an act of obedience with a personal, spiritual component. It has no power in and of itself, and certainly no Presence.

But anamnesis is not a mere passive remembering. It is an entrance into the experience of the Mystery of Christ’s sacrifice. In response, as Fr. Lawrence Farley writes in Let Us Attend, “God ‘remembers’ Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross and all that He accomplished for our salvation—that is, He makes it present and powerful in the midst of His people” (p. 72).

We cross ourselves and offer an “amen” to Christ’s sacred words of institution because this belief in His real presence in the Eucharist is foundational to the Orthodox Faith.

How does this transformation of the bread and wine occur? In the scholarly disputes of the Middle Ages, the Roman Catholic Church developed the doctrine of transubstantiation, an answer to this question of how. But the Orthodox Church has never embraced this teaching. How do the bread and the wine become the Body and Blood of Christ? A solid, Orthodox answer is, “We don’t know.” The Eucharist is both bread and wine, Body and Blood; it is simply a mystery—from mysterion, which means “sacrament”—and we leave it at that.

The Church as a Eucharistic Community

Recognizing that we can only offer to God the gifts He has already given as Creator, we kneel in reverence and thanksgiving to sing together, “We praise You, we bless You, we give thanks to You, O Lord, and we pray to You, O our God.” While we sing, the priest then prays the epiclesis, or “calling upon,” and asks God to manifest this Mystery, sending down His Holy Spirit upon the gifts of bread and wine, changing them through His power into the precious Body and Blood of Christ. He also prays for the Holy Spirit to transform us: “for vigilance of soul, for the forgiveness of sins, for the communion of Your Holy Spirit, for the fulfillment of the Kingdom of heaven.”

Father Theodore Dorrance explains,

The local church is a eucharistic community, meaning that the center of its life is the exercise of the members’ royal priesthood (1 Pet. 2:9) in the offering of their lives and all God’s creation back to Him in thanksgiving. . . . The priest offers the bread and wine back to God on behalf of the local membership of believers. God, in turn, receives this thanksgiving offering and consecrates the gifts by His Holy Spirit, changing the bread and wine into His Body and Blood (Mk. 14:22-24). The members then receive back from God His Body and His Blood, experiencing an intimate and transformative union with God (John 6:56). [from email correspondence]

Embracing the World

The next prayers in the service prepare us to reach the summit of the Eucharist. The Church looks beyond the believers standing in the nave as the priest intercedes for all people everywhere, because Christ died and rose again for all.

At this point the liturgy can begin to feel repetitive—yet again. Didn’t we pray for the world earlier? Yes, we did—right at the beginning of the service. But the world needs our prayers. We are never “finished” with our intercessions.

And we need prayer too. After praying for others, we look to our own lives in the pre-communion prayers, asking for a peaceful and sinless death, an angel to guard and guide us, and a life of peace and repentance with a Christian ending.

Point of Historical Interest: The Lord’s Prayer

Next the priest prays, “And make us worthy, Master, with boldness and without fear of condemnation, to dare call You, the heavenly God, Father, and to say…” We then respond with the familiar “Our Father, who art in heaven . . .”.

The Lord’s Prayer is the culmination of all these previous prayers, because we can only have the boldness to approach God through Christ’s forgiveness.

Let’s take a quick detour on our journey to pause at a point of historical interest: the timing of the Lord’s Prayer in the liturgy.

Jesus commanded His disciples to pray this prayer, so let’s consider why we recite it now, and not earlier in the service—or later.

The ancient Fathers spoke about the placement of the Lord’s Prayer here, right before Communion. Saint Augustine mused,

Why is [the Our Father] recited before receiving the Body and Blood of Christ? Because human fragility is such that perhaps we entertained some improper thought. . . . If perhaps such things have happened as a result of this world’s temptation and the weakness of human life, it is wiped clean by the Our Father, where it is said, “Forgive us our trespasses,” that we might approach [the Eucharist] safely. (Sermo Denis 6)

And St. John Chrysostom wrote,

At the time of the dread Mysteries, we will be able to say with a pure conscience the words of the prayer, “Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.” (Homily on Ten Thousand Talents 83)

When at last the priest elevates the Body of Christ, he cries out, “The holy Gifts for the holy people of God!” In humility we sing in response, “One is Holy, One is Lord, Jesus Christ, for the glory of God the Father, Amen,” knowing that any goodness we have comes from the holiness of Jesus Christ, for God’s glory.

Our Destination: Reception of Holy Communion

At last it is time to receive Holy Communion, and the faithful sing the communion hymn, usually Psalm 148:1: “Praise the Lord from the heavens, praise Him in the highest! Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!” We pray together the communion prayer that confesses our belief in Christ’s true presence in the elements, and we pray again for His mercy to make us worthy before we go forward.

After the clergy commune, the priest comes forward with the Chalice, chanting, “With fear of God, faith, and love, draw near.”

As we queue up, the chanters sing psalms and hymns so that we never receive Communion in silence. The timeless words of King David provide the soundtrack.

Taking in the View at a Scenic Turnout

Let’s pause again to observe the order and movement of the Church during this moment. Next time you’re in church, notice that the Chalice, filled with Christ’s sacred Body and precious Blood, is brought from the altar out to the people. Even this practical step has meaning, because the symbolism in Orthodox architecture is profound. As Fr. Theodore explains,

The solea is the place between the holy altar and the people. Just as Orthodox Christianity is the fulfillment of Judaism, so the Orthodox Christian Temple is the fulfillment of the ancient Jewish Temple. The altar corresponds to the Holy of Holies. This is the place in antiquity where the high priest annually offered and sacrificed the unblemished lamb on the Day of Atonement. Today, this is where the celebrating priest offers the perfect and bloodless sacrifice—the Lamb of God—on the holy altar table.

The solea, between the altar and the nave, corresponds to the Holy Place just outside of the Holy of Holies. The Old Testament priests offered daily sacrifices there, and in the Church, the solea is the place where holy communion is distributed to the people.

Father Theodore continues,

Symbolically, this points to the reality of our Lord’s Incarnation. Just as Christ in His divine humility was incarnated in human flesh, coming to us, so in the Divine Liturgy the chalice is brought to us on the solea, that we might partake of Him. We approach, and in a beautiful synergy He approaches us also.

Gifts of Grace

Using our baptismal names (which may be different from the names we received at birth), the priest or deacon places the spoon in our mouths, praying a blessing over us: “The servant of God (Name) partakes of the Body and Blood of Christ for the remission of sins and life eternal.”

We have now attained the summit of our journey: receiving the precious and life-giving Body and Blood of our Lord. Our use of language here is important: we receive communion; we do not take communion. The Eucharist is our Lord’s gift of Himself to us, not something we grab from Him.

Are we worthy? Of course not. And yet we pray to be made worthy.

Did we earn these Gifts by our holy lives? No way. As the communion prayer states, Christ “came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am the first.” We come to the Divine Liturgy to worship and to partake of His life, and He mystically gives Himself to us.

When the last person has received the Eucharist, the priest cries out, “O God, save Your people and bless Your inheritance.” We respond with the joyful words, “We have seen the light. . . .”

The priest returns to the Holy Table, and this final part of the Liturgy ends with a variant of the Small Litany: “Help us, save us, have mercy on us, and protect us, O Lord, by your grace.” The service comes to a close very quickly after this, with Part 9, the Dismissal.

The priest tells us, “Let us go forth in peace.” We ask him to give a blessing, and in a closing prayer, he asks for Christ’s mercy and salvation and also honors His most pure Mother and the saints who came before us.

The choir ends with a ringing Amen—“so be it”—and at last, we queue up to receive a piece of antidoron, or blessed bread.

Is the Liturgy completed? Yes. And . . . no. In some ways, it has just begun.

We leave, filled, for the liturgy after the liturgy—living out the life of Christ in the world. We will examine this concept next time in the final part of our Liturgy Quick-Start Guide.

I hope you can join me.