Over the years, I’ve heard variations of a particular message from Christian friends: Icons were created for an illiterate population, but once the Bible became available to the masses and people learned to read, we no longer needed pictures to communicate truth.

The reference to the irrelevance of religious art, or “icon worship,” was often accompanied by a patronizing tone of voice that implied that pictures are for children, not for those who are mature in faith.

I beg to differ.

The either/or perspective that pits the written word of God against iconography is a false dichotomy. Both of them feed our souls, and the Church’s use of all the senses leads us to worship God with our whole being.

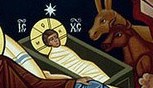

As we make our way through the Christmas season, we encounter icons of the Nativity over and over—on church bulletins, in children’s church school materials, displayed in churches and homes. The icon is familiar and comforting, yet it contains depths and mysteries worth pondering, year after year.

So let’s take a look at this icon, detail by detail, as we consider the beauty of the Incarnation of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ. This, of course, is not an original idea; I have seen many Christmastime posts in the blogosphere over the years that are devoted to icons of the Nativity. But I haven’t seen any this year, so I thought I’d cobble together a few thoughts and spread some joy.

Here is a typical icon of the Nativity of Our Lord:

![]()

The sharp, craggy rocks in the mountains and around the opening of the cave are clearly not the a depiction of the little town of Bethlehem. Instead, the barren, rough landscape symbolizes the hostile environment of our fallen, post-Eden world.

Notice the lack of the cute stable featured in most wooden creches. Instead, Christ is born in a cave, representing the darkness of sin in the world. But with His Incarnation, “the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness did not comprehend it” (John 1:4).

The entire scene is illumined by the star, which points directly to the cave:

This ray connects the star with a part of the sphere which goes beyond the limits of the icon – a symbolic representation of the heavenly world. In this way the icon shows that the star is not only a cosmic phenomenon, but also a messenger from the world on high, bringing tidings of the birth of “the heavenly One upon earth.” (Ouspensky & Lossky, The Meaning of Icons).

![]()

![]()

In the above icon and in other icons of the Nativity, the ray of light from the star has three points, representing the Holy Trinity. (See close-up on the left.) Others simply show a single ray of starlight (right).

Following the light of this miraculous star, the Magi have arrived at the cave and kneel to the reader’s left, offering their gifts to the newborn King and His Mother:

“Where is he that is born King of the Jews? For we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him.” …And when they were come into the house, they saw the young child with Mary his mother, and fell down, and worshiped him: and when they had opened their treasures, they presented unto him gifts; gold, and frankincense and myrrh (Matt. 2:2,11).

As the Troparion of Christmas states,

Thy Nativity, O Christ our God, has shown to the world the Light of Wisdom! For by it those who worshipped the stars were taught by a star to adore Thee, the Sun of Righteousness, and to know Thee, the Orient from on High. O Lord, Glory to Thee!

To the viewer’s right, the angels are worshipping Christ, but in other icons of the Nativity (see below), they hover above the scene, worshipping in the heavens while one of them announces the Good News to the shepherds:

“Be not afraid; for behold, I bring you good news of a great joy which will come to all the people; for to you is born this day in the city of David a Savior, Who is Christ the Lord. And this will be a sign for you: you will find a babe wrapped in swaddling cloths and lying in a manger” (Luke 2:10-12).

Opposite the angels, notice the young man seated on right: He is one of the shepherds, and he wears a wreath, playing a flute as he rejoices in the birth of the Savior.

The star’s light shines on the baby Jesus, who is not swaddled in the expected blanket. Instead, His wrappings are grave clothes, foreshadowing His death, burial, and Resurrection: when He was buried, Joseph of Arimathea “wrapped [His body] in a clean linen cloth” (Matt. 27:59).

Another interesting feature regarding the baby Jesus is His manger.

In some icons, Jesus’ manger is depicted as a coffin, reinforcing the prophetic imagery of His grave clothes. (Two examples are shown below.)

In other icons, His manger is depicted as an altar (close-up on right): “Now, once at the end of the ages, He has appeared to put away sin by the sacrifice of Himself” (Heb. 9:26).

Often a Nativity icon will include sheep in the background with the shepherd. But the two animals that always appear are an ox and a donkey, hovering near the manger:

Their presence is a reference to Isaiah 1:3: “The ox knows his owner, and the donkey his master’s crib.” There is a sweetness to the animals’ devotion and closeness, warming the infant Jesus with their breath. One interpretation notes that as one clean animal (ox) and one unclean animal (donkey), they represent both Jews and Gentiles, gazing at the Light of the World. These dumb animals know their Master and owner. Do we?

![]()

Now study the perimeter of the full icon at the top of this page. We see several scenes that are part of the larger Christmas story. At the top left, the Magi, looking dashing on their steeds, are following the light of the star to find the newborn King.

![]()

In the top right corner, Mary is on a horse with the Christ Child in her womb as Joseph leads them to Bethlehem. I think the figure on the left is an angel accompanying them, but I am not sure. (Let me know in the comments if you have that information.)

![]()

Now notice the two old men at the bottom left. The one with the halo is St. Joseph, hunched over and looking pensive. The other one is Satan, tempting him to doubt and unbelief. As the Protoevangelium of James teaches us (see earlier article here), he was a widower when he was betrothed to the Virgin Mary. He is portrayed here as a holy, elderly man, whereas Satan is in rags.

In some icons Joseph is near the Virgin Mary, as in the close-up on the right from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem.

But the icon above is making a theological statement by placing Joseph off to the side: He was not involved in the Incarnation, although he is the protector of Mary and Jesus. The Vespers of the Forefeast of the Nativity of Christ teaches us:

Joseph, when he beheld the greatness of this wonder, thought that he saw a mortal wrapped as a babe in swaddling clothes; but from all that came to pass he understood that it was the true God, who grants the world great mercy.

Joseph’s temptation to doubt is our own human struggle: If Jesus is truly divine, would he be born in a human way?

![]()

The icon answers this question on the bottom right, with the presence of the midwives and a vessel of water, washing the baby.

This scene emphasizes the true humanity of Jesus, who was not a spirit being who merely appeared to be human (an early heresy).

Another common but optional feature in Nativity icons is the presence of a tree.

![]()

This is not merely decorative vegetation; it is the Tree of Jesse: “A shoot shall sprout from the stump (tree) of Jesse and from his roots a bud shall blossom. The spirit of the Lord shall rest upon Him” (Isaiah 11:1-2).

In the center of the icon, not only is the incarnate Son of God present, but His Mother Mary literally looms large.

![]()

Her depiction is out of proportion; she is almost a giant among the surrounding humans and angels, kneeling or reclining in a position of honor next to her newborn Son. This is a lesson to all of us throughout history about her significance as the Theotokos, or God-bearer, chosen by God and the first in the world to receive Christ.

In many Nativity icons, she is facing Joseph in a touching display of concern: She is interceding for him in the midst of his doubt.

![]()

It is easy to understand why the Nativity icon is especially beloved in the Church, with its tenderness and depth of meaning. It is truly “theology in color,” a picture that is worth a thousand words—and more.

***

May God grant us all continued good strength in this midway point of the Nativity fast. Dr. Nicole Roccas graciously invited me to participate in her Nativity Blog-a-Thon, and you can find my post about the “messy middle” of the fasting season here. I encourage you to stop by her Time Eternal blog for daily inspiration as we approach Christmas!

If an image of one’s children, kept in wallet or purse, even years after, when these same children are grown, is worth admiration and a kiss, how much more an appreciation of the works of artists rendering their heart and faith through glass and paint?

Too fast-food are we. No time for real nourishment, forgetting that such even exists.

So true!